Bill Kovarik

“Endangered species, news, and public policy: A history,” in Communicating Endangered Species: Extinction, News and Public Policy, Eds. David B. Sachsman, Eric Freedman, Sarah Shipley Hiles, Taylor & Francis, 2021.

Abstract

Greenpeace anti-whaling demonstration, late 1970s, Pacific ocean. Photo by Rex Weyler. Used with permission.

Public concern about endangered species dates back to the early 19th century, when the very idea that a species could become extinct was a challenge for a society based on concepts of biblical creation and Aristotelian stasis. This chapter traces the history of 19th- and 20th-century media responses to news about extinction, endangered species, and the rapid decline of natural systems. It concludes that the main elements of a social response found in news coverage involved scientific discussions, ethical movements and public policy debates.

Introduction

Public concern about endangered species dates back to the early 19th century, when the very idea that a species could become extinct was a challenge for a society based on concepts of biblical creation and Aristotelian stasis.

This chapter traces the history of 19th- and 20th-century media responses to news about extinction, endangered species, and the rapid decline of natural systems. It concludes that the main elements of a social response found in news coverage involved scientific discussions, ethical movements, and public policy debates. These all played their respective parts in mediating responses to extinction and near-extinctions.

For example, 19th-century responses to rapidly declining numbers of bison led to the rise of biological surveys, then hunter-based conservation ethics movements, and then government- sponsored wildlife reserves. Similarly, ornithologists organized by the Progressive movement advanced early-20th-century tropical bird protection that was then supported by state and federal laws against bird poaching. The role of the US news media in the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) was to report and encourage each phase of the scientific, ethical, and legal response, often against social inertia but without much controversy.

However, by the early to mid-20th century, complications and conflict emerged with wildlife conservation issues, especially over federal spending. To promote reform during the New Deal era, popular journalists joined government agencies to organize agencies and advocate conservation. By the 1950s and 1960s, journalists saw environmental concerns as “the great awakening.” As the environmental movement took on new urgency, the news media moved beyond comfortable conservation columns into highly contested areas of issue advocacy and challenges to institutional architecture.

In the 1970s, in the aftermath of Earth Day and the popular embrace of environmentalism, many news organizations began to assigned reporters to permanent environmental beats. But existential questions pointed up fundamental flaws in the democratic theory of neutrally reported, factually based news coverage: What limits should be placed on the environmental agenda, and how can viewpoints be balanced, given that the next extinct species could be humanity itself?

As the volume and political impact of environmental news coverage expanded in the late 20th century, higher stakes triggered more antagonistic responses from government and industry and scorched earth tactics from right-wing political movements. While the news media sometimes served as the fulcrum between polluting industries and government regulation, a frequent industry tactic was to escalate grassroots conservative activism, undercutting the balance of environmental discourse and leaving the fact-oriented news media struggling to be heard over the din of social media.

Breaking the great chain

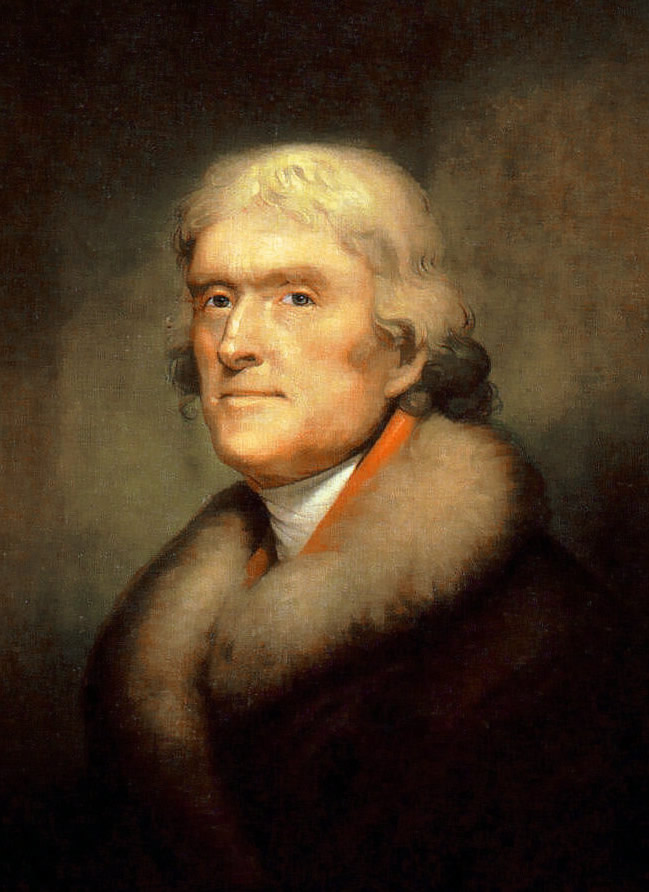

The idea that a species could become extinct was inconceivable a few hundred years ago, contradicting the long-standing biblical and Aristotelian world view of a static and permanent order of creation known as the “Great Chain of Being” (Glacken, 1976, p. 481). For example, when future US President Thomas Jefferson argued with leading French naturalist Comte de Buffon in 1787 over fossils and the alleged “degeneracy” of North American mammals, they disagreed about the size and soundness of their respective great mammals, but they were in perfect agreement about their roles in the Great Chain of Being. “Such is the economy of nature,” wrote Jefferson, “that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct” (p. 366).

The idea that a species could become extinct was inconceivable a few hundred years ago, contradicting the long-standing biblical and Aristotelian world view of a static and permanent order of creation known as the “Great Chain of Being” (Glacken, 1976, p. 481). For example, when future US President Thomas Jefferson argued with leading French naturalist Comte de Buffon in 1787 over fossils and the alleged “degeneracy” of North American mammals, they disagreed about the size and soundness of their respective great mammals, but they were in perfect agreement about their roles in the Great Chain of Being. “Such is the economy of nature,” wrote Jefferson, “that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct” (p. 366).

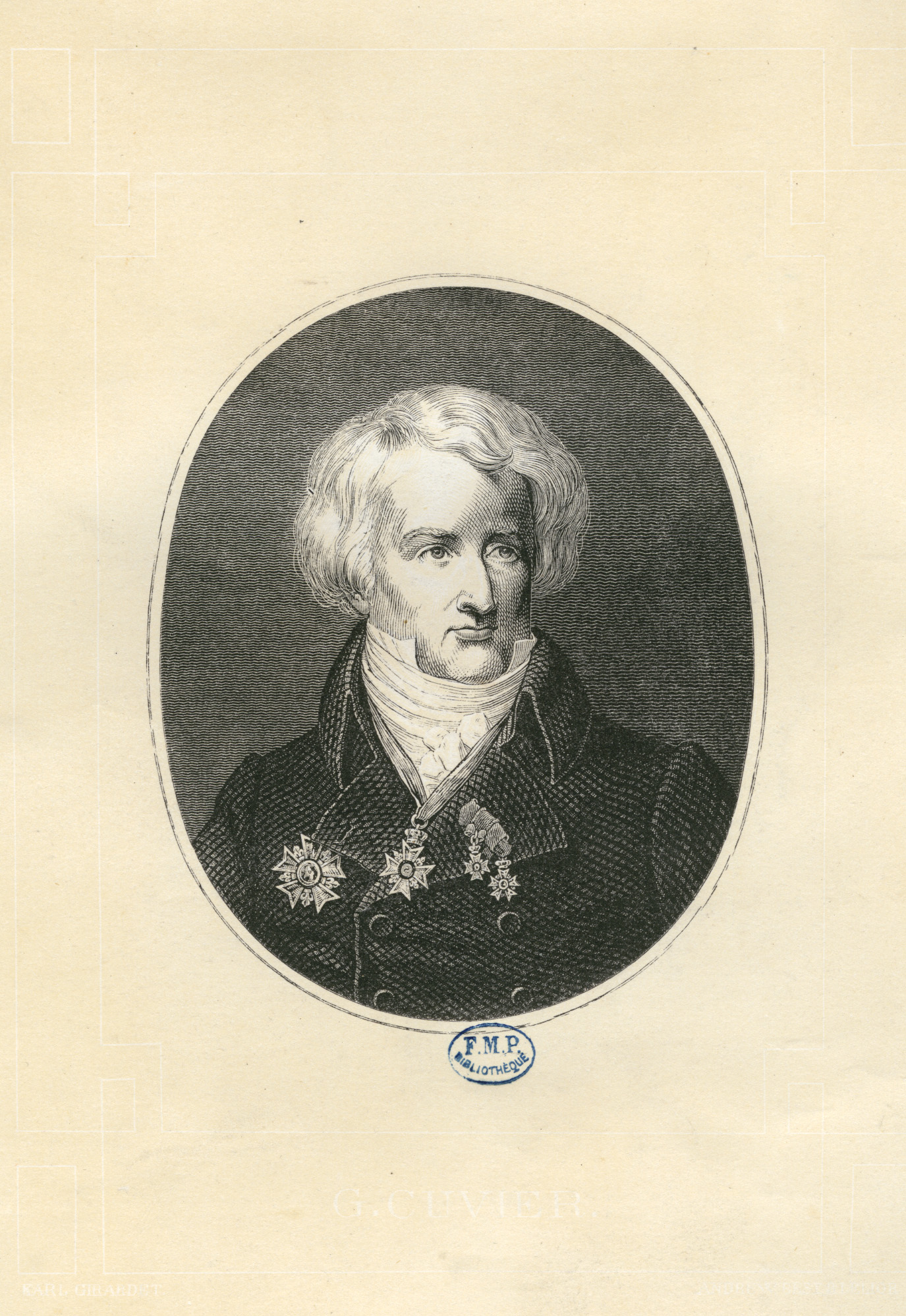

Georges Cuvier

Jefferson and most others of his era resisted the concept of extinction despite mounting evidence being compiled by another French naturalist, Georges Cuvier (Rosenberg, 2009). In a 1796 lecture, Cuvier demonstrated that unique fossils found in different geological strata around Paris could be nothing other than espèces perdues – or lost species. Cuvier analyzed thousands of fossils, along with specimens of living animals, and developed a classification system for his 1817 encyclopedic Animal Kingdom. His 1832 obituary in the Times of London noted that the book was a major influence and that he “shook to the base” (p. 5) the zoological classifications which then prevailed. When British scientists published an expanded edition of Animal Kingdom in 1835 (p. 3), the Times lauded it as a major improvement over Swedish zoologist Carl Linnaeus’s 1758 binomial classification Systema Naturae.

Scientists were not considered public figures at this time, and even sensational reports were rarely covered in the news. Richard Owen’s 1841 (p. 103) report on the remarkable fossils that he labeled “dinosaurs” was ignored by the Times of London. Later, his dioramas of prehistoric dinosaurs, presented in London and New York in the 1850s–1870s, became popular as illustrations of changing ideas about science.

But the initial accumulation of scientific facts about extinction was not the key to a profound shift in popular sentiment. That honor goes, instead, to a sensational bestselling book published in 1844, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, which broke the theological concept of the Great Chain of Being. Written in a popular style by an anonymous author, it reportedly held Victorian-era readers spellbound, presenting new ideas about the ancient origins of life as proven by geological strata and fossil finds (Secord, 2000).

“Vestiges attracted attention for the boldness with which it attacked accepted theories and conclusions,” said the Edinburgh Scotsman in 1884, 40 years after its publication. “Immediately the bigots of science and of theology rose up in anger . . . and . . . pronounced on the book a greater malediction” (New York Times, 1884a, p. 3). But science was moving on, and species extinction had become a foundation of evolutionary theory. By the 1880s, scientists and most of the public accepted the idea of extinction, if not the entirety of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Darwin’s champion, Alfred Russel Wallace, is credited in the Oxford English Dictionary as the first to give a biological meaning for the word “extinct.” “The most effective agent in the extinction of species is the pressure of other species,” the dictionary quoted him as saying (Wallace, 1880, p. 16).

Similarly, newspapers reflected acceptance of the idea around the same time. “Entire races of animals have disappeared in recent times” said a New York Times (1882, p. 6) article. Claims that wooly mammoths had been captured alive, which might not have raised a Jeffersonian eyebrow only a century beforehand, were now greeted with bemusement. If it’s true, the New York Times said, that a hunter had captured a living mammoth as he claimed, it would be “an animal wonder before whose brilliant refulgence even the white elephant must turn pale” (1884b, p. 8).

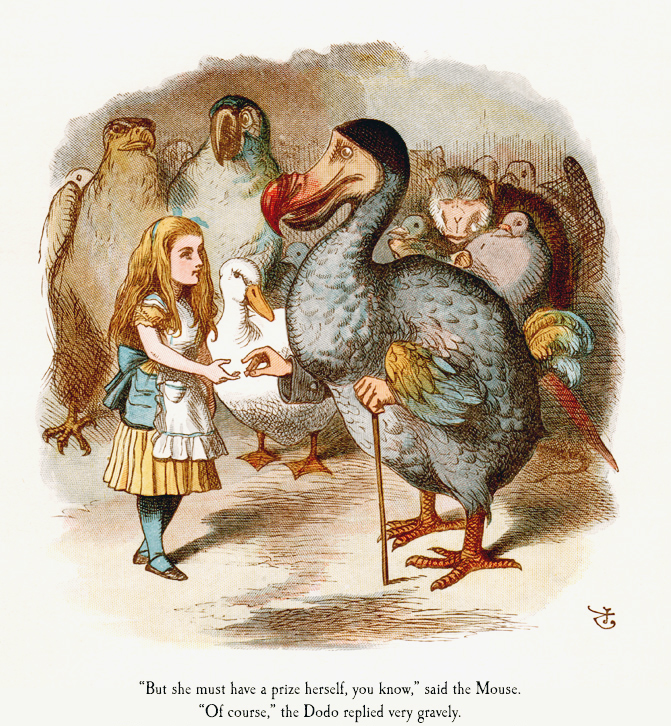

Why a dodo?

There is nothing funny about species extinction, unless it involves a flightless, hapless bird with small wings and a comically quizzical expression on its face. Linnaeus himself implicitly acknowledged the humorous nature of the dodo by calling it Didus ineptus in the 1766 edition of his book Systema Naturae (Fuller, 2002). In 1831, the dodo was said to “afford us an example of the extinction of an animal in comparatively recent times” (De la Beche, 1831, p. 154). Nor was there anything humorous about a sober and ponderous 1848 ornithological treatise, “The Dodo and its Kindred,” by Hugh Edwin Strickland and G.G. Melville. “It appears highly probable that death is a law of nature in the species as well as the individual,” Strickland said (Strickland & Melville, 1848).

There is nothing funny about species extinction, unless it involves a flightless, hapless bird with small wings and a comically quizzical expression on its face. Linnaeus himself implicitly acknowledged the humorous nature of the dodo by calling it Didus ineptus in the 1766 edition of his book Systema Naturae (Fuller, 2002). In 1831, the dodo was said to “afford us an example of the extinction of an animal in comparatively recent times” (De la Beche, 1831, p. 154). Nor was there anything humorous about a sober and ponderous 1848 ornithological treatise, “The Dodo and its Kindred,” by Hugh Edwin Strickland and G.G. Melville. “It appears highly probable that death is a law of nature in the species as well as the individual,” Strickland said (Strickland & Melville, 1848).

The following year, the Times of London appeared to be the first to employ the dodo in a humorous figure of speech. In an article about water pollution, the newspaper complained that Thames River salmon are “as extinct about Blackwall as the dodo in Madagascar” (1848, p. 4). The newspaper continued to use the dodo to great effect in following years, for example, to explain that Spanish colonialism still exists and is “no questionable dodo” (1853, p. 4).

This unusual combination of science and humor attracted so much attention that when the Oxford University Museum of Natural History opened in 1860, a dodo from its collection was one of the most popular exhibits. The dodo’s reputation as the archetype of extinction probably owed less to science and more to Oxford professor Charles Dodgson’s whimsical book, written for a friend’s daughter named Alice. Dodgson, better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll (1865), described the dodo proposing a “caucus race” after swimming in a pool of Alice’s tears in Alice in Wonderland.

Use of the dodo as a figure of speech continued in Britain with examples such as “Dodo race of real unmitigated Toryism” (Carr, 1874); a style of dress as rare as a dodo in rural France (Times of London, 1875, p. 12); and “The old dodo at Scotland Yard” (Pall Mall Gazette, 1886, p. 1).

The dodo first landed as a figure of speech on North American shores in a New York Times article (1869, p. 7) observing that good acting was “as rare as a white elephant or a dodo.” It was also used to illuminate the pending loss of “hospitable old gentlemen” (New York Times, 1875, p. 4); the “old fashioned tramp” (Washington Post, 1889, p. 10); a “political dodo – Senator [John] Jones of Nevada” (Washington Post, 1878, p. 2); the traveling circus (New York Times, 1888, p. 16); and many more.

The figure of speech didn’t go extinct after the turn of the 20th century. Novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald described dumb love with this metaphor: “Bridges had been a dodo about some YMCA man” (Turnbull, 1964). The term also was emblematic about disappearing organ grinders and monkeys (New York Times, 1924, p. X8); the National Recovery Administration’s blue eagle symbol (Bruner, 1935, p. 1); the Missouri mule (Washington Post, 1951, p. B4); a book named Such Darling Dodos (Wilson, 1950); the “vanishing” American male (Dixon, 1962, p. A15); the movie theater newsreel (Shepard, 1967, p. 37); slow pitch softball (O’Malley, 1980, p. D12); and feminist heroines (Caryn, 1989, p. H15).

Clearly, the dodo proved useful as a humorous figure of speech, perhaps symbolizing the decline of older ideas about natural stability, or a reaction to the rising encroachment of science and technology in everyday life. In any event, the dodo, as simile and metaphor, lived on for centuries past its physical extinction.

Ethical awakening

Aside from scientific discoveries and light humor, one of the most important influences on public discourse about extinction and other species involved a new ethical perspective about animal life. One starting point can be located in the lectures of Immanuel Kant, who said that a person was duty-bound to practice kindness to animals. “If he is not to stifle his human feelings, he must practice kindness towards animals, for he who is cruel to animals becomes hard also in his dealings with men” (1784).

This and similar perspectives found an institutional home with the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, established in London in 1824. (Times of London, 1824, June 17). The society existed to address the “many instances of horrid wanton cruelty which, thanks to the public press, do appear before the public,” said an 1828 (p. 3) Times of London letter calling for support for the RSPCA and signed “Humanitas.”

Around the same time, sentimental articles about animal intelligence began appearing in newspapers, such as an account of a dog rescuing another dog that was drowning (Niles Register, 1817) and a dog’s barking that saved a ship from a reef (Niles Register, 1836). By the mid- 19th century, the idea that animals had feelings and some intelligence became common in newspapers and magazines (New York Times, 1874, p. 2).

Around this same time, a broader reverence for life on earth emerged through the romantic movement in literature and art. In American literature, authors such as Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau wrote from a spiritual perspective that they found through observing the natural world. These were not always sympathetic to animal life. In Moby Dick (1851), Herman Melville described the “malevolent intelligence” of whales and said that whalers “can hardly regard any creatures of the deep with the same feelings that you do those of the shore.” In contrast, Alexander Starbuck wrote with empathy for whales in Harper’s magazine. “Imagination cannot conceive anything more awful than the butchery that now takes place. Terrified, the whale plunges from wave to wave” (1856, p. 466).

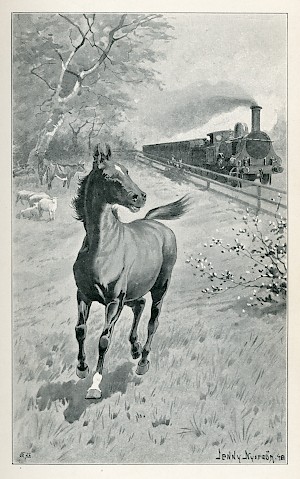

From the 1887 book Black Beauty

The strongest early expression of empathy for animals in popular literature involved a novel in the voice of a mistreated horse. Anna Sewell’s best-selling 1877 novel Black Beauty tied religion to ethical treatment of animals. “Cruelty was the devil’s own trade-mark,” she wrote in the horse’s voice:

and if we saw anyone who took pleasure in cruelty we might know who he belonged to, for the devil was a murderer from the beginning, and a tormentor to the end. On the other hand, where we saw people who loved their neighbors, and were kind to man and beast, we might know that was God’s mark.

A similar distinction between cruelty and compassion emerges in Sarah Orne Jewett’s 1886 short story, “A White Heron,” in which the heroine expresses:

sorrow at the sharp report of [a hunter’s] gun and the sight of thrushes and sparrows dropping silent to the ground, their songs hushed and their pretty feathers stained and wet with blood. Were the birds better friends than their hunter might have been, – who can tell? Whatever treasures were lost to her, woodlands and summer-time, remember!

Many other works of fiction, including Wind in the Willows, White Fang, Jungle Book, Doctor Doolittle, and Mark Twain’s “A Dog’s Tale,” were published in the late 19th and early 20th century, allowing allowed readers to achieve higher levels of empathy with the natural world. Through romantic and ethical perspectives, the door was also opened to non-fiction nature writing by authors such as John Muir, John Burroughs, Florence Merriam Bailey, and Edward Howe Forbush.

Science occasionally came into conflict with the animal ethics movement, especially in Britain, around questions concerning the cruelty of vivisection experiments on living animals. Between 1903 and 1910, opponents of these experiments (called “doggers”) and medical students (“anti-doggers”) fought in street riots, in the courts, and around symbols such as statues of dogs (Rupke, 1987).

Teddy Roosevelt refuses to shoot a bear cub, 1906.

During this period, American hunters also began to embrace a new kind of ethic that included preservation and habitat protection. One example was US President Teddy Roosevelt’s refusal to kill a bear cub in an incident covered by newspapers at the time and depicted in a political cartoon (Washington Post, 1902, p. 1). The incident inspired the much-loved stuffed toy, the Teddy Bear.

This idea of an expanding ethical understanding of the natural world also served as the main theme of Aldo Leopold’s 1948 classic book, A Land Ethic. The origin of ethics, Leopold said, involved relationships between individuals that were guided by great moral codes such as the Ten Commandments. An expanded ethical understanding involved relationships between individuals and society, exemplified by the Golden Rule. Now, an ethic was needed to deal “with man’s relation to land and to the animals and plants which grow upon it” (Leopold, 1949). The trend line for the news articles that described efforts to protect the natural world in the late 19th and 20th century follows this expanding circle of ethical understanding.

Trail of the bison

The concept of extinction was first regarded with curiosity and mild humor, but the American public and press became alarmed at the rapid loss of the vast herds of bison in the late 19th century, and this aroused public opinion saved the remaining herds in the early 20th century.

Originally, the bison were the great icons of the frontier and a background presence in early American literature for authors like Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper. There were so many that it seemed impossible for them to go extinct. “

At any time [before] 1836, a traveler might start at any point north or south in the Rocky Mountain range. . .[and] his road would always be among large bands of buffalo, which would never be out of view,” said explorer John C. Frémont (Niles Register, 1845). But by 1845, the buffalo started to occupy “a very limited space,” he wrote. “The extraordinary rapidity with which the buffalo is disappearing from our territories will not appear surprising when we remember the great scale on which their destruction is yearly carried on.”

At any time [before] 1836, a traveler might start at any point north or south in the Rocky Mountain range. . .[and] his road would always be among large bands of buffalo, which would never be out of view,” said explorer John C. Frémont (Niles Register, 1845). But by 1845, the buffalo started to occupy “a very limited space,” he wrote. “The extraordinary rapidity with which the buffalo is disappearing from our territories will not appear surprising when we remember the great scale on which their destruction is yearly carried on.”

New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley was able to see the last of the great herds on his 1859 “Overland Journey” to California. “All day yesterday, they darkened the earth around us, often seeming to be drawn up like an army in battle array on the ridges and down their slopes a mile or so south of us,” Greeley wrote on May 31, 1859. “What strikes the stranger with most amazement is their immense numbers. I know a million is a great many, but I am confident we saw that number yesterday” (Greeley, 1860, p. 87).

Like Greeley, young future president Roosevelt (1893) also traveled west and wrote of his bison hunts. “Their numbers were countless – incredible,” he wrote.

Like Greeley, young future president Roosevelt (1893) also traveled west and wrote of his bison hunts. “Their numbers were countless – incredible,” he wrote.

In vast herds of hundreds of thousands of individuals, they roamed from the Saskatchewan to the Rio Grande and westward to the Rocky Mountains. After the ending of the Civil War, the work of constructing trans-continental railway lines was pushed forward with the utmost vigor. Several million buffaloes were slain. In 15 years from the time the destruction fairly began, the great herds were exterminated.

Roosevelt’s concern about the bison exemplified a new ethic of sportsmanship championed by a new breed of “sporting journals” led by Forest and Stream, established in 1873 by Charles Hallock and edited by George Bird Grinnell (Neuzil & Kovarik, 1996). Hallock helped form the New York Association for the Protection of Game in 1874, while Grinnell helped spark state Audubon societies and the Boone and Crockett club for hunters and conservationists.

A few people contradicted the calls for conservation, but not many. In one case, the superintendent of Yellowstone National Park insisted the herd of 200 bison was well protected and would not go extinct (Washington Post, 1888, p. 2).

By the 1890s, conservationists were sounding dire warnings not only in specialized publications and sporting journals but also in mainstream newspapers. When William T. Hornaday, the superintendent of the National Zoo in Washington, DC, wrote “The Extermination of the American Bison,” his subsequent lectures and ideas were carried in newspapers around the country (Washington Post, 1890, p. 8). Hornaday remained a leading scientific voice for saving bison and other endangered species through the early part of the 20th century. He was widely quoted in the press, for example, decrying the “unprecedented slaughter” of the bison in the New York Times (1896, p. 20). The alarm escalated towards the turn of the century. Bison extermination was “The Crime of the Century” according to an 1899 Scientific American article by Charles Frederick Holder, a naturalist and author. It is “a pitiful story of the greed of the white man and the extirpation of a mighty race within three decades” (p. 378).

Articles about the beasts quadrupled between the 1870s and 1880s, then doubled again in the 1890s. At the height of the Progressive Era’s interest in bison, more than 9,000 articles ran in the Washington Post, New York Times, Baltimore Sun, and Wall Street Journal between 1890 and 1900, while another 20,000 ran between 1901 and 1910. Magazine writers such as Robert Underwood Johnson of Century Magazine warned that what happened to the bison could happen elsewhere, reflecting an enormous increase in interest about endangered or exterminated species.

The American Bison Society was established in 1905 with Hornaday as its president to preserve what was left of the bison herds. President Roosevelt encouraged preservation of the bison, and by 1908, the US Fish & Wildlife Service established the National Bison Range in Montana. Remnants of the herds were saved, and the warnings of the bison hunters proved not to be entirely in vain.

A New York Times editorial said Hornaday “deserves the gratitude and encouragement of the nation as the chief preserver from extinction of the American bison” (1907, p. 8). Reaffirming the need for such efforts, Roosevelt’s National Conservation Commission reported that game and fur bearing animals were “largely exterminated” (National Conservation Commission, 1909). The movement to save the bison had gone from science to ethics to regulation in one short generation.

Protecting birds from “murder for millinery”

“To be fashionable, one must be extreme,” a Washington Post writer declared in 1907. Women’s hats should be “laden with feathers . . . in tremendous proportions” (p. 16). Feathers from flamingos, egrets, pelicans, pheasants and crowned pigeons (goura) were especially favored. And yet, if this meant beauty to some, it meant revolting cruelty to others. Starting in the 1870s, George Bird Grinnell and Forest and Stream magazine began to kindle a movement to stop the trade in feathers and the mass slaughter behind it.

“To be fashionable, one must be extreme,” a Washington Post writer declared in 1907. Women’s hats should be “laden with feathers . . . in tremendous proportions” (p. 16). Feathers from flamingos, egrets, pelicans, pheasants and crowned pigeons (goura) were especially favored. And yet, if this meant beauty to some, it meant revolting cruelty to others. Starting in the 1870s, George Bird Grinnell and Forest and Stream magazine began to kindle a movement to stop the trade in feathers and the mass slaughter behind it.

Calls for restraint and bird protection laws flooded American newspapers and magazines by the 1890s and early 1900s. Three approaches made up the broad social movement:

- Ethical questions were raised by Women’s clubs and the Audubon societies which urged a boycott of fashionable feathered hats, often as an appeal to “higher womanhood” or avoidance of “murder for millinery.” (Price, 1999);

- Scientific and educational groups, such as university ornithologists and the Smithsonian Institution, gave a view of the scope of the problem and the logic of reform;

- Advocates of government regulation, such as Roosevelt and Hornaday, provided a practical framework for reform.

An example of the ethical approach involved news coverage of a talk by Reverend O.P. Gifford, who described the egret plume in a woman’s hat as a “brand of shame on thoughtless women” (Washington Post, 1897a, p. 7). Mark Twain’s daughter, Jean L. Clemens, made “an earnest plea” to save the birds in 1906, writing that men “will shoot anything and everything that they can hit . . . Is there nothing to be done?” (Baltimore Sun, 1906, p. 10). And similarly, in 1899, then-governor of New York Theodore Roosevelt compared killing birds with vandalism.

The destruction of the wild pigeon and the Carolina parquet has meant a loss as severe as if the Catskills or the Palisades were taken away. When I hear of the destruction of a species I feel just as if all the works of some great writer had perished. (New York Times, 1899, p. 7). This ethical approach eventually led to the 1905 formation of the National Audubon Society from a variety of state level Audubon groups. The organization took the name of America’s most famous artist and ornithologist, John James Audubon (1785–1871), whose Birds of America, printed between 1827 and 1838, is among the world’s great treasures in print (Audubon, 1827).

The second approach, using an educational and scientific strategy, involved assessments of damage and logical arguments to the effect that birds could be beneficial because, for example, they eat insect pests. Edward Howe Forbush, an ornithologist who wrote Useful Birds and Their Protection, focused on their practical benefits and protection strategies. Institutions often added their weight to the educational arguments. The Smithsonian Institution supported this approach, as the Washington Post reported in 1897. “It declares that civilized man is sweeping the wild birds off the face of the earth at such a rate that before long, hardly any species of feathered creatures will survive save those which are domesticated” (p. 17).

The third approach involved state and federal regulation to provide legal protection for threatened resources. US Representative John F. Lacey of Iowa stepped forward with the Lacey Bird and Game Act of 1900. The bill made transportation of bird skins and feathers a violation of federal law. Hat makers complained that the Lacey Act “has proven to be a serious blow” and threatened to put them out of business (New York Times, 1903, p. 3). All three approaches worked together, but the ethical argument protected birds through peer pressure and effectively turned the tide. Women stopped wearing bird feathers in their hats and, by 1912, Paris fashion designers decreed that rare plumes would no longer adorn spring hats.

According to the New York Times: Following the example of some American states, and for the first time in the history of Paris fashions, ostrich plumes and feather of other beautiful and valuable birds are to be barred from the newest models of women’s hats next season. (1912, p. C5) The Audubon Society later suggested feathers from domestically raised birds as a substitute (Washington Post, 1940, p. 17).

The movement to protect birds led to human losses along the way. When two poachers killed Audubon game warden Guy Bradley on July 8, 1905, the news received wide coverage by the national press (Baltimore Sun, 1905). Poachers also killed game warden Columbus G. McLeod in Florida and Audubon Society employee Pressley Reeves in South Carolina in 1908. Twenty-five years later, retired Miami Herald editor Marjorie Stoneman Douglas wrote a short story, “Plumes,” for the Saturday Evening Post, that described the emotions of Bradley’s killer. “It was only weakness and sentimentality in him to flare up so at the idea of killing birds,” she wrote (1930, p. 8).

Extinction of the passenger pigeon, 1914

Another major milestone in the news about extinctions was the death of Martha, the last passenger pigeon, in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. Her photo graces the first page of Hornaday’s book, Our Vanishing Wildlife, which quotes ironically from an 1858 Ohio state report: “The passenger pigeon needs no protection. Wonderfully prolific. . .no ordinary destruction can lessen them, or be missed from the myriads that are yearly produced” (Hornaday, 1913).

Another major milestone in the news about extinctions was the death of Martha, the last passenger pigeon, in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. Her photo graces the first page of Hornaday’s book, Our Vanishing Wildlife, which quotes ironically from an 1858 Ohio state report: “The passenger pigeon needs no protection. Wonderfully prolific. . .no ordinary destruction can lessen them, or be missed from the myriads that are yearly produced” (Hornaday, 1913).

As it turned out, the vast flocks of pigeons were decimated in a little less than 40 years, and again, the reaction was dismay at the slaughter (Greenberg, 2014). One Indiana farmer who had killed pigeons to protect his crops when he was young found that they had stopped coming as he grew older. He wrote in Forest and Stream: “Perhaps we were too prodigal as a people with our abundance, and a kind Providence took [the pigeons] away to teach us wisdom” (Hussey, 1914, p. 6). Martha’s death led to widespread introspection in the press.

When we talk of extinct animals, we think of creatures like the mammoth or mastodon, which died out thousands upon thousands of years ago. We seldom realize that there are whole species which have vanished quite lately, and many which are at present just trembling in the balance. (Washington Post, 1915, p. MS 3)

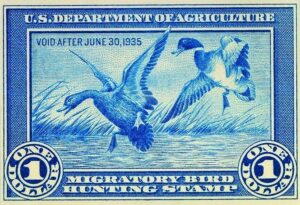

Concerns about extinction led to the Migratory Bird Treaty of 1918 and the Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940, yet lax enforcement meant that illegal traffic in wild bird plumage continued (New York Times, 1940, p. 23).

Conservation and the New Deal

As the dust settled after World War I, old heroes retired with honors and new issues arose to vex conservationists. In a 1925 White House ceremony, journalist and wildlife advocate George Bird Grinnell received the Roosevelt Memorial Association Medal for his work in wildlife conservation. Forester and then Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot also received the award (New York Times, 1925, p. 23).

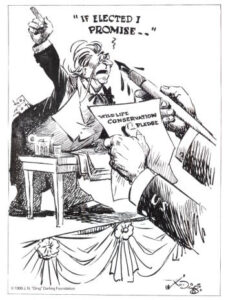

The new issues included a need to sort through the patchwork of state hunting regulations, and the election of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932 brought hope that the New Deal could coordinate conservation policies. Congress passed half a dozen conservation laws early in the New Deal, but conflicts over direct funding meant that they had to be set up with self-funding mechanisms. For example, improved habitats for ducks received funding through the federal “duck stamp” tax on duck hunting. In 1933, Roosevelt created a Migratory Bird Conservation Committee to help guide the programs, chaired by Collier’s magazine editor Thomas H. Beck. The committee included wildlife management expert and ethicist Aldo Leopold, along with cartoonist Jay “Ding” Darling, who had set up a similar committee in Iowa (Cart, 1972, pp. 113–120).

The new issues included a need to sort through the patchwork of state hunting regulations, and the election of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932 brought hope that the New Deal could coordinate conservation policies. Congress passed half a dozen conservation laws early in the New Deal, but conflicts over direct funding meant that they had to be set up with self-funding mechanisms. For example, improved habitats for ducks received funding through the federal “duck stamp” tax on duck hunting. In 1933, Roosevelt created a Migratory Bird Conservation Committee to help guide the programs, chaired by Collier’s magazine editor Thomas H. Beck. The committee included wildlife management expert and ethicist Aldo Leopold, along with cartoonist Jay “Ding” Darling, who had set up a similar committee in Iowa (Cart, 1972, pp. 113–120).

Based at the Des Moines Register, “Ding” was a nationally syndicated cartoonist from 1900 to 1962 who earned two Pulitzer Prizes for cartooning. He also designed the first duck stamp. Ding’s prominent conservation advocacy led Roosevelt to appoint him as head of the US Biological Survey in 1934, but he quit a year and a half later because Congress was “deaf to his appeal for funds.” He also expressed dismay at the New Deal’s still-disorganized conservation program:

Based at the Des Moines Register, “Ding” was a nationally syndicated cartoonist from 1900 to 1962 who earned two Pulitzer Prizes for cartooning. He also designed the first duck stamp. Ding’s prominent conservation advocacy led Roosevelt to appoint him as head of the US Biological Survey in 1934, but he quit a year and a half later because Congress was “deaf to his appeal for funds.” He also expressed dismay at the New Deal’s still-disorganized conservation program:

Conservation as a national principle has no substance or co-ordination. . ..Fourteen agencies in the Federal Government and forty-eight states . . . are like so many trains running on single-track roads, often in opposite directions and without any train dispatcher or block system. Collisions are frequent, wrecks are a daily occurrence, and the destruction is greater than the freight delivered at the specified destination. (Darling, 1935, p. 5)

After leaving the Biological Survey, Darling chaired a 1936 North American Wildlife Conference in Washington with the idea of unifying the various forces he said were so confused. “In his ringing style of delivery, Darling drew a picture of polluted lakes and slaughter-house hunting grounds, the result of wild-life neglect and misuse,” the Washington Post reported (1936, p. 15). The result was an organization initially called the General Wildlife Federation, with Darling as its first president. It became the National Wildlife Federation in 1938 and attracted millions of members in the following decades.

Another conservation-minded journalist in the mid-20th century was Edward Meeman, an editor with the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain in Tennessee and the chain’s main conservation editor. He was known especially for his crusade on behalf of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and support of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s conservation programs. Other writers covering conservation in the interwar years included Richard Oulahan, whose 18-part series starting May 12, 1940, was about “nature and nature groups in Washington.” The series began:

Picture these United States without a tree . . .. The story of the destruction of America’s great natural resources is a familiar one. On every hand are examples, mute testimony to the ruthlessness of human beings who despoiled and exploited the outdoor wealth of the continent. Acres of stumps where once were limitless forests; dust bowls born of fertile plains; birds animals and fish passing each year into extinction. (Oulahan, 1940, p. AM6)

World War II and postwar era conservation news coverage

Conservation writing was a back-bench occupation during World War II, and although congressional hearings on wildlife conservation continued, they were rarely covered. One reporter observed wryly that far less hunting and fishing was going on in 1944, and that the war had turned out to be a silver lining for the Fish and Wildlife Service conservation policy (McBride, 1944, p. S4). Occasional wildlife stories were framed in terms of the war effort in the 1940s. “During the pressure of war there is grave danger that conservation may lose ground; ground [that had been] gained through a hard struggle over a period of many years” (Oscher, 1943, p. L5).

Postwar years

The postwar years were a time for taking stock, and three books along those lines rose to prominence. The Everglades: River of Grass (1947) by former Miami Herald editor Marjory Stoneman Douglass described the history and wildlife of the Florida Everglades. Like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring 15 years later, the book became a classic of environmental literature.

Another, Our Plundered Planet by New York Zoological Society chief Fairfield Osborn (Osborn, 1948) was a Malthusian guide to post-war life. It was appreciated in later years for its early opposition to pesticides and as part of the birth of global ecology. (Robertson, 2012).

William Vogt’s 1948 Road to Survival is a summary of the world’s diminished ecological status, describing US history as a “march of destruction.” The Washington Post called him a “pious Malthusian” with a gift for sardonic epigrams (Lalley, 1948, p. 6). However, Vogt’s comments on the decline of natural systems in Africa and Latin America were apropos, given the renewed US commitment to internationalism, and the establishment of the International Union for Conservation of Nature in 1948. The IUCN was not well covered at first, except for a short New York Times story about the UNESCO conservation conference in Lake Success the next summer (1949, p. 31).

Later, as the problem of international conservation was acknowledged, John B. Oakes of the New York Times began addressing conservation as “A World Problem.” He wrote: “The rapid disappearance of big game in America is, unfortunately, being paralleled in other continents right now” (1956, p. 101). As both a reporter and editorial page editor at the Times, Oakes brought conservation news to a higher level. He also was one of the few who made the transition to the more aggressive world of environmental reporting. In 1994, the Natural Resources Defense Council established an award for environmental journalism in his name.

The idealistic 1960s

The shift from “conservation writing” to “environmental journalism” occurred gradually over the 1960s, but one starting point was a 1961 speech by newly inaugurated President John F. Kennedy to the National Wildlife Federation. “It is our task,” Kennedy said, “to protect those resources for future generations – to hand down undiminished the natural wealth and beauty which are ours today” (Casey, 1961, p. A2).

The charm of the Kennedy administration brought new stars to conservation causes, from aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh (Whitman, 1969, p. 1) to Prince Phillip of Britain (Kihss, 1980, p. B3) to actress Brigitte Bardot (Whittington, 1983, p. A1). All these and many more turned up in the media as advocates for endangered species during the late 20th century’s environmental revolution.

The most celebrated was Rachel Carson, the author of Silent Spring, which was the most influential piece of environmental reporting of the era. A former writer with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Carson was concerned about the unintended effects of pesticide misuse on birds. She struck a nerve even though the basic news about misuse of pesticides had already been covered (Washington Post, 1960, p. 1).

In an August 1962 press conference, President Kennedy was asked whether government agencies should study the growing concern over DDT. He replied, “Yes, and I know that they already are, and I think particularly of course of Miss Carson’s book, but they are examining the matter” (New York Times, 1962, p. 10). “This was a cleaving point,” wrote Carson biographer William Souder, “the moment when the gentle, optimistic proposition called ‘conservation’ began its transformation into the bitterly divisive idea that would come to be known as ‘environmentalism’” (2012, p. 5).

Like “Ding” Darling, many journalists who wrote in the gentle, optimistic voice of conservation began a transformation of their own. These included John B. Oakes, Gladwin Hill, and E. W. Kenworthy of the New York Times, syndicated columnist Drew Pearson, and Washington Post writer George Wilson (Neuzil & Kovarik, 1996). Pearson brought his nephew’s concerns for wildlife into his columns as a nod to a younger generation’s idea that saving animals was more important than politics (1964, p. B25).

As wildlife preservation became popular, it also became far more political. New controversies broke out about advocacy and environmental journalism. “Any media reporting of an environmental issue is advocacy, in the sense that media coverage draws attention to that issue,” Philip Tichenor and Mark Neuzil wrote in Nieman Reports in 1994. “Airing a crisis that pits loggers against spotted owls lends the issue a measure of legitimacy” (Tichenor & Neuzil, 1996).

Ann Cottrell Free of the Baltimore Sun saw conservation coverage turning into a crisis. “Our giant of a nation is stirring,” she wrote in 1969. “It is in the early stages of a Great Awakening. Not only are some of us wondering about the implications of [DDT in] eagle’s eggs, many of us are realizing that our fouled air and water could soon come seeded with destruction for the human race.

(p. WK6).

Oakes caught the new spirit of environmental debate when he wrote in a 1979 column that the false and reckless charges over the economic impact of environmental lawsuits were evidence that “McCarthyism still lives” (p. A27). One issue he singled out was the 1978 Tellico Dam controversy, which “destroy[s] more in natural values than it can possibly create in artificial ones.” The dam project in Tennessee had been stalled in part due to the presence of endangered snail darter fish. Congress approved construction of Tellico, overriding its own endangered species laws. However, Congress refused similar calls for exceptions to the law, especially for the New River in western Virginia and North Carolina. Kenworthy, another Times reporter whose main beat was the environment, began one article on the New River dam controversy by quoting US Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: “A river is more than an amenity; it is a treasure” (1974).

Saving cetaceans

Any big species on the verge of extinction is likely to be the focus of news reports, and that’s especially true of charismatic megafauna like whales and dolphins. As early as 1910, a New York Times editorial endorsed the idea of whale conservation. “Now that the bison is saved from extinction,” the paper said, scientists were calling for “the rescue of his warm-blooded cousin of the ocean plains” (New York Times, 1910, p. 8).

International studies about whale conservation began in 1924 with a League of Nations conservation committee, and League members signed a treaty pledging an effort to conserve whales (New York Times, 1932, p. XX3). A similar set of studies, followed by a similar international commitment, was reported in 1948 (New York Times, 1948, p. 28). When the International Whaling Commission acknowledged that blue whales were nearly extinct in 1965 (Bevona, 1965, p. A31), calls for a halt to whaling came not only from the commission and the IUCN, but also from conservation groups around the world (Hill, 1969, p. XX23). The US government banned importation of whale products in 1970 by listing whales as endangered species. Whaling was mostly banned internationally in 1986.

Little opposition to wildlife conservation is evident in the news media until the 1970s, when politically conservative reactions to environmental issues started popping up in the press. Concern for whales was nothing more than an “emotional squabble,” wrote Norman Pearlstine of the Wall Street Journal. “Whale meat, in Japan, is poor man’s beef,” and banning whale hunting there would be like banning cattle ranching in America, he said (Pearlstine, 1974, p. 36).

Amid increasing acrimony, activists were determined to use the media to change the environmental debate. An upstart group from Vancouver, British Columbia, started using nonviolent tactics to put themselves between harpoons and the whales they hoped to save. “For the first time in the history of whaling, human beings had put their lives on the line for whales,” wrote Charles Flowers (1975, p. 192), a book critic for the New York Times, who found attempts to save whales ironic historically, noting that in the 19th century, “American whalers were as bloodthirsty as any.”

Flowers and many others missed the point of the new activism. The idea, said Robert Hunter, was to create a “mind bomb” – that is, an action that would create a dramatic new impression and replace an old cliché. In this case, that meant overturning the image of heroic whalers and replacing it with the image of heroic ecologists risking their lives to save the gentle giants of the sea.

Greenpeace caught the world’s attention and dramatically changed the political terrain for the media and the environmental movement (Kovarik, 2010). Partly as a result, public opinion research showed that environmentalism was “one of the most successful contemporary movements in the US and Western Europe” (Mertig & Dunlap, 1995, p. 145). Of course, whales were not the only charismatic species studied while under threat of extermination. Diane Fossey, a scientist and crusader for preservation of mountain gorillas in Africa, was famous for her 1983 book, Gorillas in the Mist. Her 1985 murder in Rwanda was widely covered in the world press (Battiata, 1986, p. C1).

News coverage expanded with more dramatic events occurring. “The late 1980s and early 1990s were salad days for the environmental beat,” as Neuzil wrote in his book The Environment and the Press (2008, p. 196).

With that growth came challenges and problems, some of which sounded familiar to those who had been in the field for decades . . . many stories still suffered from poor sourcing. . .some stories were superficial and under-reported; and dramatic events still took precedence over harder-to-understand environmental problems.

One antidote to superficial event-oriented news was the establishment of the Society of Environmental Journalists in 1990.

A harbinger of difficulties to come was Phil Shabecoff’s forced retirement from the New York Times. “I resigned because I was taken off the environmental beat in 1990 because my coverage about things like climate change was considered alarmist,” he said (Bravender, 2018).

Shabecoff’s successor on the beat, Keith Schneider, was frequently criticized from both the conservative and liberal sides of environmental debates. In one particularly controversial article about dioxin, a toxic chemical blamed for human and animal deaths, Schneider wrote that exposure “is now considered by some experts to be no more risky than spending a week sunbathing” (1991, p. A1). The key word was “some” experts, and the article also included sharply critical points of view about dioxin from scientists with a different point of view, indicating that the controversy was unsettled.

However, Schneider was widely criticized for including the “sunbathing” remark. USA Today environment editor Rae Tyson said: “I think Schneider messed up. It was not because he questioned a time-honored premise, but because he relied on some questionable science to prove his point” ( Monks, 1994). In any event, the controversy benchmarked the increasingly complex field for environmental news coverage.

Meanwhile, just as environmental reporting dealt with more controversy and complexity, time and space for environmental stories began shrinking. In 2004, Sharon Friedman, a professor of science and environmental communication at Lehigh University in the United States, warned that environmental news coverage was dropping quickly, especially in smaller newspapers. Still, the quality of environmental journalism was generally positive, she said (2004, p. 175).

In the first decades of the 21st century, environmental reporting faced a counter-movement against environmental science fueled by right-wing conspiracy theories. These included racist misinformation about DDT use (Milloy, 2007); misinformation about United Nations environmental treaties (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2014); and, especially, efforts to depict the science around climate change as fraudulent (Oreskes & Conway, 2010).

By the end of the second decade of the 21st century, the watchdog group Public Citizen warned that news about climate science in the right-of-center Fox News media was being deliberately crafted “to undermine climate science, cast climate advocates as hysterical and frame climate policy as dangerous and un-American” (Hartman, 2020). Worse, right-wing environmental advocates spread the racist belief that the root cause of environmental destruction is overpopulation by non-white people.

The media also suffered major setbacks to the capacity and credibility of environmental journalism in the early 21st century. CNN management, for example, dismissed its entire Science and Technology team in 2008. Another setback involved the dismantling of the New York Times environmental desk in 2013 (Brainard, 2013). In both cases, the explanation involved financial pressures. However, in both cases, sources close to the situation said the pressures were political, not financial. “They’ve made a horrible decision that ensures the deterioration of the Times’s environmental coverage at a time when debates about climate change, energy, natural resources, and sustainability have never been more important to public welfare,” said Curtis Brainard of the Columbia Journalism Review.

Still, many news organizations did face significant financial problems. National Geographic Society’s The Green Guide ceased publication in 2008; E Magazine stopped print production in 2013; Pacific Standard closed in 2019; and an overall decline in coverage reflected the financially distressed media environment of the early 21st century.

By the 2020s there was reason for hope. Support for environment in public opinion polls held steady at over 70 percent (Gallup, 2021). The New York Times had renewed its commitment to environmental coverage by establishing a climate desk in 2017, and, during the 2020 election, a collaborative effort by 400 publications covered the impacts of climate change worldwide (Tracy, 2019, p. B1; Hertsgaard & Pope, 2020). The idea was to “tell the climate story so people can get it,” a Columbia Journalism Review article said (Hertsgaard & Pope, 2019).

Mark Hertzgard, the collaborative’s editor, said:

Despite the “climate silence” that had long prevailed in much of the media, especially in the US, we sensed that there was a critical mass of journalists and news outlets that recognized the need to do better. If we could highlight this critical mass, we thought, we could grow it.

Conclusion

This historical portrait of news about endangered species shows that media coverage changed through several historical periods. During the Progressive movement around the turn of the 20th century, the press responded to the facts of extinction by covering scientific discussions, ethical movements, and debates over public policy responses. As a part of the New Deal of the 1930s, several major figures in the press joined the Roosevelt Administration to help guide public policy. A consensus about conservation meant that very little public controversy took place, and writers focused on the decline in resources, for example, at the start of Washington Post writer Richard Oulahan’s 1940 series: “Picture these United States without a tree.”

Coverage changed again from the post-war years to the 21st century, as the underlying focus shifted from declining natural resources to the link between wildlife and human survival. For example, the Baltimore Sun’s Ann Cottrell Free warned in 1969 that “fouled air and water could soon come seeded with destruction for the human race.”

More than fifty years later, news organizations carried similar warnings from scientists and international officials about the link between biodiversity and human existence, for example, in this March, 2021 op-ed carried by CNN: “The scientific evidence calls for a complete change — a total overhaul of our relationship with nature and biodiversity. This is not an option, but a necessity for our survival.” (Azoulay, 2021).

References

Audubon, J. J. (1827–1838). Birds of America. Edinburgh: Havell.

Audrey Azoulay, Jane Goodall, et al. (2021). Our survival depends on treating nature with more respect. CNN March 24, 2021. Accessed at: https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/24/opinions/biodiversity-nature-survival-azoulay-lee-salgar/index.html

Baltimore Sun. (1905, August 6). His life to save birds.

Baltimore Sun. (1906, December 26). Wants birds saved.

Battiata, M. (1986, January 25). Murder and the private war: Dian Fossey. Washington Post.

Bevona, D. (1965, May 2). Blue whale nearly extinct. Washington Post.

Brainard, C. (2008, December 4). CNN cuts entire science, tech team. Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved fromhttps://archives.cjr.org/the_observatory/cnn_cuts_entire_science_tech_t.php

Brainard, C. (2013, March 1). New York Times cancels Green blog. No explanation from editors following surprise announcement. Columbia Journalism Review.Retrieved from https://archives.cjr.org/the_observatory/new_york_times_cancels_green_e.php

Bravender, R. (2018, December 14). Pioneering environment writer wants an apology. E&E News. Retrieved from www.eenews.net/special_reports/offtopic/stories/1060109689

Briggs, H. (2020, June 2). “Extinction crisis poses existential threat to civilization,” BBC. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-52881831

Bruner, F. (1935, March 23). Richberg taking NRA helm. Washington Post.

Carr, L. (1874). Judith Gwynne. London: H.S. King & Co.

Carroll, L. (1865). Alice’s adventures in wonderland.London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cart, T. W. (1972). New deal for wildlife. Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 63(3), 113–120.

Caryn, J. (1989, July 16).Are feminist heroines an endangered species? New York Times.

Casey, P. (1961, March 4). President pleads for wildlife. Washington Post.

Darling, J. N. (1935, October). Desert makers. Country Gentleman, 105.

De la Beche, H. T. (1831). A geological manual. London: Treuttel and Würtz.

Dixon, G. (1962, July 4).The vanishing American male. Washington Post.

Douglass, M. S. (1930, June 15). Plumes. Saturday Evening Post.

Douglass, M. S. (1947). The everglades: River of grass. New York: Rinehart & Co.

Flowers, C. (1975, August 24). Between the harpoon and the whale. New York Times.

Fossey, D. (1983). Gorillas in the mist. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Free, A. C. (1969, April 13). The great awakening: City hall, congress and the white house. Are aware of our battle for survival. Baltimore Sun.

Friedman, S. (2004). And the beat goes on: The third decade of environmental reporting. In S. Senecah (Ed.), Environmental communication yearbook (Vol. 1). Mawah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Fuller, E. (2002). Dodo – from extinction to icon. London: Harper Collins.

Gallup Inc. (2021). Environment. Accessed https://news.gallup.com/poll/1615/environment.aspx

Glacken, C. (1976). Traces on the Rhodian shore. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Greeley, H. (1860). An overland journey from New York to San Francisco, in the Summer of 1859. New York: C.M. Saxton Barker & Co.

Greenberg, J. (2014). A feathered river across the sky. New York: Bloomsbury.

Hartmann, B. (2020, Spring). The ecofascists. Columbia Journalism Review.Retrieved from www.cjr.org/special_report/ecofascists.php

Hertsgaard, M., & Pope, K. (2019, July 26).Can we tell the story so people get it? Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved from www.cjr.org/covering_climate_now/covering-climate-partnerships.php

Hertsgaard, M., & Pope, K. (2020, September 23). The media’s climate coverage is improving but time is very short. Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved from www.cjr.org/covering_climate_now/the-medias-climate-coverage-is-improving-but-time-is-very-short.php

Hill, G. (1969, January 19). Cetacean society has whale of a job. New York Times.

Holder, C. F. (1899, September 9). The crime of a century. Scientific American.

Hornaday, W. T. (1913). Our vanishing wildlife. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Humanitas. (1828, July 3). To the editor of the “Times”. Times of London.

Hussey, T. (1914, March 21). Days of passenger pigeons. Washington Post.

Jefferson, T. (1787, April). Comparative view of the animals of America and those of Europe. Columbian Magazine.

Jewett, S. (1886). A white heron and other stories. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Kant, I. (1784[1997]). Moral philosophy: Collin’s lecture notes (P. Heath & J. B. Schneewind, Eds. & Trans., pp. 37–222). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kenworthy, E. W. (1974, December 8). The nation in summary. New York Times.

Kihss, P. (1980, October 2). Plea for wildlife made in speech by Prince Philip. New York Times.

Kovarik, B. (2010). Greenpeace. In S. H. Priest (Ed.),Encyclopedia of science and technology communication. Los Angeles: Sage.

Lalley, J. M. (1948, August 16). The books that last. Washington Post.

Leopold, A. (1949). A Sand County almanac and here and there. New York: Oxford University Press.

McBride, T. M. (1944, March 12). War may be aiding fish, wildlife service’s conservation policy. Washington Post.

Melville, H. (1851). Moby Dick or the whale. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Mertig, A., & Dunlap, R. (1995). Public approval of environmental protection. International Journal of Public Opinion Research,7(2).

Milloy, S. (2007, June 9). The malaria clock: A green eco-imperialist legacy of death. Junkscience.com.

Monks, V. (1994, August). The truth about dioxin. National Wildlife Federation.Retrieved from www.nwf.org/Magazines/National-Wildlife/1994/The-Truth-About-Dioxin

National Conservation Commission. (1909). Report of the national conservation commission.60th Congress, 2nd Session, Senate Document No. 676. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Neuzil, M. (2008). The environment and the press: From adventure writing to advocacy. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Neuzil, M., & Kovarik, W. (1996). Mass media and environmental conflict, America’s green crusades. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

New York Times. (1869, September 21). Amusements, theatrical, Miss Bateman as Lear.

New York Times. (1874, January 2). Some new stories about animals.

New York Times. (1875, August 2). Extinct characters. Reprinted from the Richmond Whig.

New York Times. (1882, March 19). Entire races extinct.

New York Times. (1884a, May 4). Newsy foreign gossip. Reprinted from the Edinburgh Scotsman.

New York Times. (1884b, September 18). Science to be surprised.

New York Times. (1888, January 22). Going to join the dodo.

New York Times. (1896, July 26). Killing of the bison.

New York Times. (1899, March 24). To protect the birds.

New York Times. (1903, February 16). Bird dealers protest.

New York Times. (1907, November 3). Bison preserves.

New York Times. (1910, November 1). Conservation of whales.

New York Times. (1912, January 28). Rare plumes won’t adorn spring hats.

New York Times. (1924, November 16). Organ grinders and monkeys.

New York Times. (1925, May 16). Coolidge Presents Roosevelt Medals.

New York Times. (1932, April 24). Nations signing whale treaty pledge conservation efforts.

New York Times. (1940, October 16). Illegal traffic in plumage scored.

New York Times. (1948, November 27). World whale pact is ratified by US.

New York Times. (1949, August 24). Nature umpire urged on animal, plant life.

New York Times. (1962, August 30). Transcript of the president’s news conference.

Niles Register. (1817, March 22). Sagacity of a dog,pp. 12, 60.

Niles Register. (1836, October 1). Value of a dog,pp. 51, 80.

Niles Register. (1845, September 20). Capt. Frémont’s report,pp. 45, 69.

Oakes, J. B. (1956, July 18). Conservation: A world problem. New York Times.

Oakes, J. B. (1979, December 28). Saving the web of life. New York Times.

O’Malley, P. (1980, July 10). Girls keeping fast-pitch alive. Washington Post.

Oreskes, N.,& Conway, E. M. (2010). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. New York: Bloomsbury.

Osborn, F. (1948).Our plundered planet. New York: Little Brown & Co.

Oscher, P. H. (1943, May 9). The squandered wealth of a nation. Washington Post.

Oulahan,R. (1940, May 12). Wildlife Federation fights to save nation’s heritage. Washington Post.

Owen, R. (1841, July). Report on British fossil reptiles. Part II. Report of the eleventh meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Pall Mall Gazette. (1886, February 11). The old dodo at Scotland Yard.

Pearlstine, N. (1974, June 26). Wailing over whaling: Angry Japanese see effort to stop killing. Wall Street Journal.

Pearson, D. (1964, July 20). Man to blame for extinct species. Washington Post.

Price, J. (1999). Flight maps: Adventures with nature in modern America. New York: Basic Books.

Robertston, T. (2012, April). “Total War and the Total Environment: Fairfield Osborn, William

Vogt, and the Birth of Global Ecology,” Environmental History 17: 336–364.

Roosevelt, T. (1893). Hunting the grisly and other sketches. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Rosenberg, G. D. (2009). The revolution in geology from the renaissance to the enlightenment. McLean, VA: Geological Society of America.

Rupke, N. (1987).Vivisection in historical perspective. London: Croom Helm.

Schneider, K. (1991, August 15). US Backing away from saying dioxin is a deadly peril. New York Times.

Secord, J. (2000). Victorian sensation: The extraordinary publication, reception and secret authorship of vestiges of the natural history of creation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sewell, A. (1877). Black Beauty, his grooms and companions, the autobiography of a horse. London: Jarrold & Sons.

Shepard, R. (1967, December 22). The movie newsreel flickers its last and dies. New York Times.

Souder, W. (2012). On a farther shore; the life and legacy of Rachel Carson. New York: Crown.

Southern Poverty Law Center. (2014). Agenda 21: The UN, sustainability and the right wing conspiracy theory. Retrieved from www.splcenter.org/20140331/agenda-21-un-sustainability-and-right-wing-conspiracy-theory

Starbuck, A. (1856). The story of the whale. Harper’s, 12.

Strickland, H. E., & Melville, A. G. (1848). The dodo and its kindred or, the history, affinities, and osteology of the dodo, solitaire, and other extinct birds of the islands Mauritius, Rodriguez and Bourbon. London: Reeve, Benham, and Reeve.

Tichenor, P., & Neuzil, M. (1996, Winter). Advocacy, the uncomfortable issue. Nieman Reports, 41.

Times of London. (1824, June 17). Society for the prevention of cruelty to animals.

Times of London. (1832, August 29). Cuvier.

Times of London. (1835, January 24).Cuvier’s animal kingdom.

Times of London. (1848, September 14). London is a city.

Times of London. (1853, May 25). There are two things in antiquity.

Times of London. (1875, June 9). The late Comte de Remusat.

Tracy, M. (2019, July 8). Newsrooms face a changing climate. New York Times.

Turnbull, A. (Ed.). (1964). The letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald(1sted.). London: Bodley Head.

Vogt, W. (1948). Road to survival. New York: William Sloane.

Wallace, A. R. (1880). Island life: Or, the phenomena and causes of insular faunas and floras,including a revision and attempted solution of the problem of geological climates. London: Richard Clay and Sons.

Washington Post. (1878, February 18). Personal.

Washington Post. (1888, August 24). Buffalo and elk will not become extinct.

Washington Post. (1889, July 21). The talking machine.

Washington Post. (1890, January. 4). A war of extermination.

Washington Post. (1897a, February 14). Taking final flight.

Washington Post. (1897b, April 12). Pleads for the birds.

Washington Post. (1902, November 15). Tied up a bear but failed to shoot it. Reprinted from the Baltimore Sun.

Washington Post. (1907, September 24).Fall opening at Kann’s.

Washington Post. (1915, April 4). Animals man has wiped out.

Washington Post. (1936, February 4). Darling talks at wild life session.

Washington Post. (1940, December 13). Bird massacre for millinery opposed.

Washington Post. (1951, October 22). Missouri mule on the wane.

Washington Post. (1960, December 27).Pesticides blamed: Census finds bald eagle vanishing from capital.

Whitman, A. (1969, June 23). Lindbergh traveling widely as conservationist. Washington Post.

Whittington, L. (1983, February 24). Europe’s threat halts Canadian seal pup hunt. Washington Post.

Wilson, A. (1950). Such darling dodos. London: Secker & Warburg.