Chapter 3 in Routledge Handbook of Environmental Journalism, Eds. David B. Sachsman, and JoAnn Myer Valenti, Routledge, 2019.

Abstract

The story of environmental journalism tends to focus on North America and Europe. Nevertheless, reporters in Asia, Africa, and Latin America have a long history of responding to their own environmental issues. This chapter disproves the myth that the developing world is “too poor to be green.” The author takes us from Brazilian journalist Euclides da Cunha in 1902, to the Philippines in 1908, to India in 1950, and then to the newspaper coverage, extraordinary photographs, and television documentary about Minamata disease in Japan from 1954 to 1971. He describes the coverage of the Green Revolution in India, the rise of environmental journalism in China, and the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant disaster in Japan. He notes that “environmental beats have turned out to be among the most dangerous in journalism, especially in the global South where the news media of most countries is either partly free or not free,” and reports that “the space for environmental journalism is shrinking” in India, as it is in the West.

Introduction

Environmental journalists in Asia, Africa, and Latin America have struggled for over a century to bring limited resources to bear on complex public health and natural resource issues, often in situations where international forces overwhelm their own countries.

This historical survey summarizes observations and studies about the general history of environmental journalism in developing nations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. It also describes some of the individual journalists who have struggled and sometimes died to advance democracy and environmental understanding.

In the past, studies of environmental issues and information systems have focused heavily on Europe and North America. The myth that no real environmental movement or journalism existed in the developing world rested on the assumption that it was “too poor to be green” (Guha & Martínez-Alier, 1997, as if environmentalism and reporting on the environment were the exclusive preoccupations of the wealthy.

However, a closer look shows that environmental problems are associated with, and not separate from, issues of poverty, human rights, and under-development. An understanding of how the long chain of history ties these problems to present dilemmas must also include international as well as separate national forces. Often enough it is the legacy of colonialism, exploitation, and racism to which the original environmental problems can be traced.

“Indigenous people often do not realize what is happening to them until it is too late. More often than not, they are the victims of the actions of greedy outsiders,” said Ken Saro-Wiwa, a Nigerian journalist who stood up to the oil industry and was executed by a Nigerian military dictatorship.

Sometimes an apparent conflict between the ideals of environment and development is a problem. “To ask for any change in human behavior – whether it be to cut down on consumption, alter lifestyles or decrease population growth – is seen as a violation of human rights,” said Indian journalist Lyla Bavadam. “[However], it’s time we changed our thinking so that there is no difference between the rights of humans and the rights of the rest of the environment. Environmental journalism has a role to play in this change” (Bavadam, 2010, p5).

Although a history of environmental journalism across a region so vast and varied does not lend itself to easy generalizations, environmental journalists in the developing world face issues that are similar to their counterparts in Europe and North America, including advocacy, education, access to information, and funding support.

However, journalists in the developing world must also face more difficult situations regarding press freedom and human rights. Journalists are increasingly subject to a rising level of harassment, imprisonment, and assassination from corrupt regimes hoping to keep their misdeeds out of the glare of publicity.

Many journalists in the developing world are refusing to be cowed, and new initiatives to protect them are emerging through non-governmental groups, news organizations, and the United Nations and related agencies Kapchanga, 2016

Early environmental journalism

The 20th century began with nearly all of Asia and Africa subjected to colonialism, which meant not only direct rule by European powers, but also a mass media usually controlled in the colonial interest. Sometimes, hair-raising stories would emerge of genocidal exploitation, as from the Congo or Peru, as we will see. Neocolonialism and economic dependency characterized most Latin American nations. While their military struggles for independence took place in the 19th century, economic independence was still in question.

In the 20th century, as independence movements arose around the world, two great world wars and a global financial crisis allowed colonial powers to put off rising demands for independence until the end of World War II.

Between the 1940s and the 1960s, as dozens of new nations began to pursue their own destinies, the newly freed media looked outward, to the United Nations and other international efforts, to understand paths to development and environmental protection. They also looked inward.

The idea of protecting nature and public health had deep roots in Asian, African, and Latin American religious and cultural traditions. In some countries, such as India, the idea of environmental protection preceded the Progressive era reform movements in Europe and North America. In other countries, journalists have struggled simply to bring their stories out to the rest of the world.

The “Belgian” Congo

Reporting on the genocidal exploitation of native people working on rubber plantations in central Africa and the upper Amazon during the late 19th and early 20th centuries might be among the most significant, if not earliest, examples of environmental reporting in the developing world.

Human rights issues stood out, along with exploitative rubber and ivory harvesting, as Edmund D. Morel (1904) investigated what he called “a bad and wicked system inflicting terrible wrongs upon the native races” in what was then known as the “Belgian” Congo. Morel documented many cases where rubber plantation workers who did not work fast enough to suit plantation owners had their hands amputated.

Along with books such as King Leopold’s Rule in Africa, Morel founded the West African Mail in 1903 and carried on an active campaign to change the occupation of the Congo by a private company answerable to no one. It is now estimated that half of Congo’s 20 million population in 1890 were killed or died from causes related to the 20-year private occupation (Hochschild, 1998). Even though Congo’s problems became known in Europe and the US, the extent of ongoing prejudice was such that the author of a 1910 Washington Post editorial could blame “ignorant natives” for the ruthless exploitation and criminal destruction of rubber and other natural resources in central Africa. (Washington Post, Sept. 18, 1910).

Added post-publication note: The Crime of the Congo — written by Arthur Conan Doyle in 1909 — should also be considered here. Doyle gives full credit to Edmond D. Morel’s difficult work for human rights. Doyle also notes: “The crime which has been wrought in the Congo lands by King Leopold of Belgium and his followers [is] the greatest which has ever been known in human annals.”

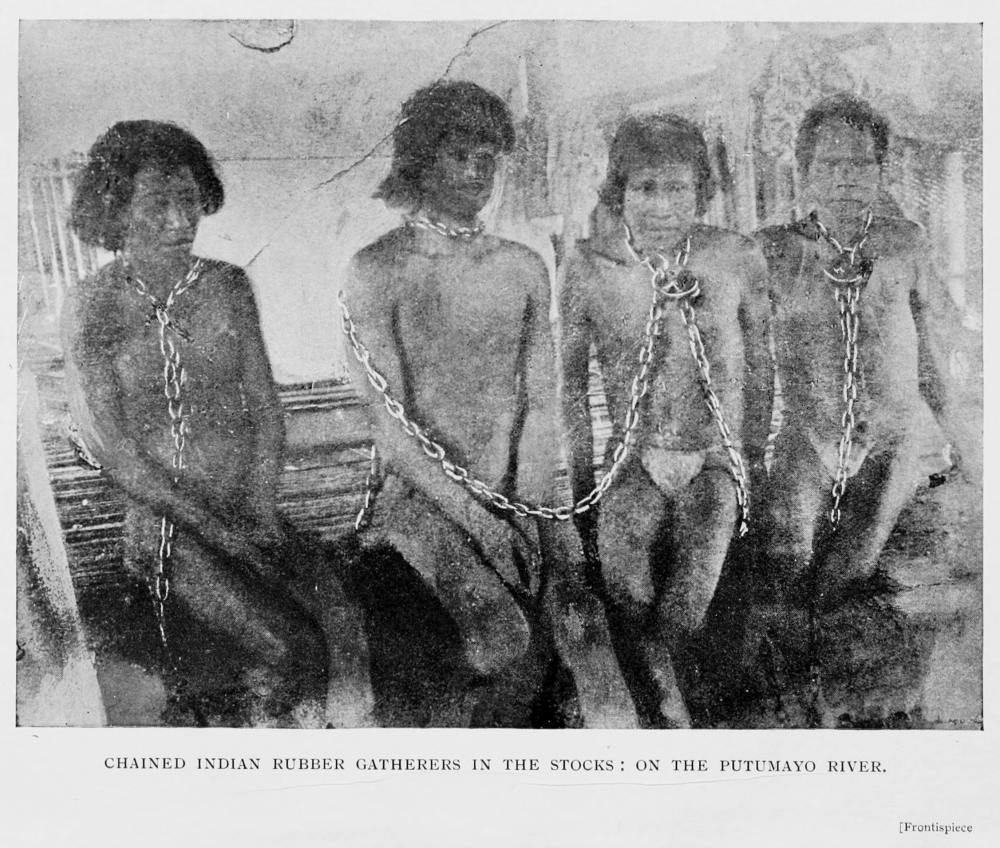

Peru: the Devil’s paradise

Around 1907 in Iquitos, Peru, the same kinds of human rights abuses were occurring in the Amazonian rubber-growing industry. Benjamin Saldaña Rocca, a Peruvian businessman, demanded justice from the courts. When his demands were met with silence, he founded La Sanción, a newspaper that would cover the problems. “Because their rubber deliveries fall short of the required weight, [Peruvian natives] are shot, or their arms and legs are cut off with machetes,” Rocca quoted an eyewitness in a 1907 exposé entitled “The Devil’s Paradise: A British-Owned Congo.” The article was reprinted in London two years later, after the newspaper was closed down and Rocca was forced into exile by Peruvian authorities.

Around 1907 in Iquitos, Peru, the same kinds of human rights abuses were occurring in the Amazonian rubber-growing industry. Benjamin Saldaña Rocca, a Peruvian businessman, demanded justice from the courts. When his demands were met with silence, he founded La Sanción, a newspaper that would cover the problems. “Because their rubber deliveries fall short of the required weight, [Peruvian natives] are shot, or their arms and legs are cut off with machetes,” Rocca quoted an eyewitness in a 1907 exposé entitled “The Devil’s Paradise: A British-Owned Congo.” The article was reprinted in London two years later, after the newspaper was closed down and Rocca was forced into exile by Peruvian authorities.

In both the Congo and Peru, the exposés of genocidal exploitation led to international investigations but no immediate changes or criminal charges. Meanwhile, the journalists who brought the exposés to the public were only able to continue their work in Europe.

Protecting natural resources

The centuries-old idea of Brazil as an “Eden” helped fuel an early 20th-century campaign by scientists and journalists for public protection of natural resources. One leader was Brazilian journalist Euclides da Cunha, who in 1902 wrote Os Sertoes (Rebellion in the Backlands) about the environment of the central coast and a rebellion in the Canudos region.

The centuries-old idea of Brazil as an “Eden” helped fuel an early 20th-century campaign by scientists and journalists for public protection of natural resources. One leader was Brazilian journalist Euclides da Cunha, who in 1902 wrote Os Sertoes (Rebellion in the Backlands) about the environment of the central coast and a rebellion in the Canudos region.

The fight between modern and traditional ways of life, cast against the backdrop of Brazil’s apparently limitless forest, is the book’s theme. Da Cunha believed that people are molded by climate. He also “saw clearly the fundamental problems of modern societies: that they weren’t essentially different from the societies they defined as traditional and that their supposed universalism was often a cloak for particular interests” (as quoted in Celarent, 2012).

Da Cunha set the stage for a sustained campaign, organized by scientists and journalists, that resulted in 1934 in the First Brazilian Conference on the Protection of Nature, a legally protective Forest Code, and the creation of the nation’s first national parks (Corrêa, 2010).

India’s tree huggers

Long before industrialism and mass media, advocates for nature were in conflict with India’s government. In 1730, for example, more than 350 Bishnoi people of what is now Jodhpur, India, were killed as they hugged khejri trees in an attempt to protect them from a maharaja’s woodsmen. They were the original “tree huggers,” and their inspiration came not only from their need for the forest but also from the ancient Hindu and Buddhist doctrine of Ahimsa, concerning non-violent compassion for all living things.

Forest conservation was remarkably well organized under the 19th-century British Raj in India, inspiring the creation of European and US government forestry services. It also helped inspire Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy linking the Ahimsa doctrine to the India independence movement and resistance to British colonialism. A prolific writer, Gandhi, as early as 1909 in his book Hind Swaraj (Indian Home Rule), pointed to air and water pollution as products of unrestricted industrialism and materialism (Kaushik, 2018). “If India copies England, it is my firm conviction that she will be ruined. . . . Where this cursed modern civilization has not reached, India remains as it was before,” Gandhi (1909) wrote, advising a correspondent to “go into the interior that has not been polluted by the railways.”

Gandhi and the Bishnoi tree-huggers provided inspiration for the modern Van Mahotsav (“forest festival”) tree-planting movement, begun in 1950 by Kanaiyalal Manekial Munshi, a journalist and follower of Gandhi, and continuing today as a week-long tree-planting celebration. The Bishnoi incident was also an inspiration for a revival in the 1970s of the Chipko forest preservation movement in the Himalayan highlands. Munshi also helped organize one of the UN conferences on natural resources in 1952 in Lucknow, India. At the time, petroleum was thought to be running out, but Munshi said it would be wrong to use ethanol from grain and root crops. Instead, research was needed on ways to make fuel from non-food crop wastes (Munshi, 1952).

Gandhi and the Bishnoi tree-huggers provided inspiration for the modern Van Mahotsav (“forest festival”) tree-planting movement, begun in 1950 by Kanaiyalal Manekial Munshi, a journalist and follower of Gandhi, and continuing today as a week-long tree-planting celebration. The Bishnoi incident was also an inspiration for a revival in the 1970s of the Chipko forest preservation movement in the Himalayan highlands. Munshi also helped organize one of the UN conferences on natural resources in 1952 in Lucknow, India. At the time, petroleum was thought to be running out, but Munshi said it would be wrong to use ethanol from grain and root crops. Instead, research was needed on ways to make fuel from non-food crop wastes (Munshi, 1952).

Philippine resistance

Like editors in Africa and Latin America, a Philippine newspaper editor’s resistance to exploitative colonialism stands out as an early example of environmental journalism. A 1908 editorial by Philippine journalist Fidel A. Reyes called “Birds of Prey” attacked the occupying US government’s plundering of mineral and marine resources. Reyes also exposed the sale of unhealthy meat, directed by corrupt American officials.

Reyes used an eagle as the American symbol and said he “ascends the mountains . . . to study and civilize [rural people] . . . at the same time, he also espies during his flight, with the keen eye of the bird of prey, where the large deposits of gold are, the real prey concealed in the lonely mountains.” In response, one US official not even named in the articles brought a libel suit against El Renacimiento. This led to the permanent closure of the newspaper.

Kenyan wildlife conservation

The example of wildlife conservation in Africa provides another insight into the deep reach of colonialism. The first attempts at wildlife preservation involved hunting reserves established in Kenya and South Africa around 1900. When an international conference was held in London in November of 1900, agreements on hunting restrictions in Africa were forged between “the seven great European powers” (Washington Post, Dec. 11, 1900). No African nation was represented. It was only in 1973 that international agreements on curbing trade in African wildlife could be negotiated by African countries themselves or reported, without censorship, in the African press (Facts on File, 1973).

Until the 20th century, most African newspapers were published by a European-based reform movement, or religious organization, or a colonial government (Barton, 1979). Independent newspapers were slow in coming, but in Kenya, the Muigwithania (meaning “reconciliation”) newspaper, established in 1928 by future president Jomo Kenyatta, provided a voice for Kenyan independence and the return of land confiscated by white colonialists.

Even with an independent newspaper, however, colonial interests guided long-term wildlife preservation, and many of the great parks and wildlife conservation efforts were conceived in isolation. The establishment of the Nairobi National Park in Kenya in 1946, 15 years before independence, involved removal of native Maasai pastoralists, which is today seen not only as an injustice but also a misunderstanding of a complex ecology (Pearce, 2010). Issues of conservation continued to be seen in the West through the rose-colored colonial lens with books and films like the 1959 book The Serengeti Shall Not Die or the 1966 film Born Free.

Often there was no one to contradict colonial fables or provide the African viewpoint, even in the independent press. In the 1960s and 1970s, Kenyan newspapers stayed loyal to Jomo Kenyatta and did not expose his family’s involvement with the illegal ivory trade and ruby mining in Tsavo National Park (Maloba, 2018; Kamau, 2009).

Post-World War II – international frameworks

Although developing nations shared the same kind of conservation and public health problems faced by European and North American nations, resources for identifying and dealing with environmental problems were not as available. International institutions provided the most important early framework for understanding environmental concerns in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Following World War II, one of the first items on the agenda of the new United Nations was to organize international conferences on conservation and the environment. The perception had been that resource scarcity and mismanagement had been a contributing cause of financial instability and war. When the first conference took place in September 1949, US President Harry S. Truman explained that “conservation can become a basis of peace” (Schmidt, 2019, p. 107). The UN Scientific Conference on the Conservation and Utilization of Resources was one of two UN conferences that year highlighting concerns about the conservation of land, water, forests, wildlife and fish, fuels, energy, and minerals.

World media were flooded with pre-conference prints of 500 scientific papers along with radio programs broadcast in 16 languages. Similarly, the International Geophysical Year of 1957–1958 generated news coverage of scientific discoveries around the world, and again, widespread media coverage was encouraged.

However, the weakness of the market-oriented global media, reflected in the nearly complete dominance of US, British, French, and Russian wire services (AP and UPI, Reuters, AFP, and TASS, respectively) meant that information alternatives were needed for developing nations. In practice, this meant that a newspaper or radio station in Nigeria would have far more access to information about American or Russian science than, for example, information about research in Ghana or Venezuela.

Media within the international framework

One response to this global imbalance of information was the establishment of the Inter News Service (IPS) in 1964. It was intended, founder Roberto Savio said, to give a voice to those absent in the traditional flow of information, including: “women, indigenous peoples and the grassroots, as well as issues such as human rights, environment, multiculturalism, international social justice, and the search for global governance” (Savio, 2014).

When a path-breaking United Nations conference on the environment took place in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1972, one of the major goals was to provide more environmental education through world information systems. The conference recommended:

. . . that the Secretary-General make arrangements: (a) To establish an information programme designed to create the awareness which individuals should have of environmental issues and to associate the public with environmental management and control. This programme will use traditional and contemporary mass media of communication, taking distinctive national conditions into account. In addition, the programme must provide means of stimulating active participation by the citizens, and of eliciting interest and contributions from non-governmental organizations for the preservation and development of the environment (United Nations, 1972).

As a result, the United Nations Environmental Program created Infoterra, a repository for scientific information about the environment and a news service designed to catalyze environmental protection from the top levels of government down to the grassroots in the developing world. Infoterra started in 1977 at a time when access to information was far more difficult than in the 21st century. A 1980 paper described Infoterra as “a unique international cooperative effort in the field of environmental information exchange” (Villon, 1980). Although it had defenders, it was also criticized for slow return on information queries, low rates of use, and high costs (Aronczyk, 2018). The service was closed in 2003.

Infoterra and IPS became seen as examples of how difficult it was to improve global information systems. Information sent through telegraph wire services, newspapers, and radio broadcasting almost always moved from the global North to the South. Development experts saw a need for increased flow of communication from South to South and from South to North, and the Infoterra experience became part of the rationale for the McBride Commission study on structural imbalances in global communication systems.

The Commission recommended the establishment of a New World Information and Communication Order that restructured the flow of communication for the sake of development (Brendebach, Herzer, & Tworek, 2018). Western wire services and conservative governments fought any government or UN control over communication, while many developing nations struggled to create their own domestic news and culturally appropriate information and entertainment.

For environmental information, several other major international efforts began in subsequent years. Internews is a foundation-funded news service started in California in 1982 and originally focused on film and television broadcasting about issues associated with nuclear war. Internews expanded in 2003 to include the Earth Journalism Network, which has connected and trained over 4,500 journalists covering environmental issues around the world. Also, TierrAmerica, an IPS service created following the 1992 United Nations Rio conference, was established to cover Latin American environmental issues. In 2015, the UN’s “Integrated Regional Information Network” launched as an independent, nonprofit media venture to cover humanitarian crises (IRIN, 2019).

United Nations agencies, development banks, and private foundations regularly assist in environmental, science, and agricultural journalism training and networking. Usually, the focal points for the training conferences are journalism organizations such as Inter Press Service, Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, the Society of Environmental Journalists, the World Federation of Science Journalists, or nationally based environmental and science journalism groups.

“The level of activity may ebb and flow with the vagaries of funding and transitions in leadership,” said James Fahn, executive director of the Earth Journalism Network. “These are the two main challenges: obtaining consistent funding, and ensuring good leadership. In fact, these issues are often related. Unlike [the US-based SEJ], they generally can’t rely on membership dues to thrive, or even survive, and [in the Global South] there aren’t the many philanthropic options that we have in the Global North.”

Much of the development through the UN and US agencies is going to general democracy-building programs, and is not specifically earmarked for environmental journalism, said Meghan Parker, executive director of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Environmental news agenda expands 1950s-1980s

The United Nations conferences on the environment in the late 1940s and early 1950s were built around an agenda of natural resource conservation issues. However, other issues were emerging in the postwar era. Some were well known, like air and water pollution control. Others were new, such as the environmental effects of agricultural pesticides, toxic wastes, and contamination from atmospheric nuclear tests.

All of the issues were seen through two very different ideas about development and journalism: On the one hand, the idea of development journalism was that journalists would serve the goals of the newly independent governments without criticism that might weaken the development efforts. On the other hand, there was the idea that journalists were obliged to act as a watchdog on government power (Ogan, 1980).

The contrast between an authoritarian and a libertarian philosophy of communication has had an influence on the way environmental journalism is seen. Many journalists in developing countries who have criticized polluting industries or government regulations have paid a high price.

In 1950s Japan, for example, mainstream journalists were accustomed to an authoritarian system, and it was only through alternative media that the public understood the outlines of Minamata disease. And in 1960s Brazil, the authoritarian system alienated mainstream journalists and made some of them more determined to press ahead with environmental reporting.

Minamata disease in Japan in the 1950s

Perhaps the most unexpected issue was the emergence of a strange form of poisoning first reported in the Japanese cities of Minamata and Kumamoto, southwest of Tokyo. As early as 1954, a local newspaper carried a story about a strange malady affecting cats with loss of motor control, almost as if they were dancing.

In April 1956, doctors in Minamata were alerted to patients with symptoms ranging from permanent numbness to severe birth defects. Dr. Hajime Hosokawa reported “an unclarified disease of the central nervous system.” Through a series of tests, Hosokawa soon narrowed the cause of the disease to dumping of methyl mercury by the Chisso Corporation. The government refused permission for Hosokawa to publish his tests (Togashi, 1999).

On April 1, 1957, Asahi Shimbun, a leading national daily newspaper, first reported a “strange disease” of the central nervous system, with 17 deaths and another 54 people hospitalized. The blame was laid to some kind of “toxic metals . . . contained in waste solutions of chemical products.” Neither Chisso nor the mercury in fish diets were mentioned (Asahi Shimbun, 1957).

The Chisso Corporation and MITI, Japan’s trade ministry, worked actively to deflect attention from real problems. MITI told Chisso to install an effluent treatment system in 1959, and then encouraged news reports that implied that the system would help. However, MITI and Chisso both knew that the system was not designed to remove mercury and Chisso was able to continue mercury dumping until 1968 (Japan Ministry of the Environment, 2013).

Meanwhile, fishermen and others began protesting the government’s inaction, and this led to some news coverage in the early 1960s. Since traditional news media were somewhat constrained from challenging the government, alternative media began to fill the gap.

In the summer of 1960, a young photographer named Shisei Kuwabara arrived in Minamata. He faced an ethical dilemma in that victims were reluctant to have their photos taken, but he returned again and again over 40 years to document the problem. He won a series of Japanese and world press photojournalism awards.

Japanese filmmaker Noriaki Tsuchimoto, concerned that a 1960s television documentary about Minamata had been superficial, produced a more in-depth 1971 documentary, “Minamata: The Victims and their World,” in which patients afflicted by mercury poisoning were given a voice in the media. “He let the victims speak for themselves, giving their side of the story, which was not being represented in the mass media or recognized by Chisso or the government. He did not just show their plight to others, but worked to show his films in the area to educate other victims” (Yasui & Gerow, 1995).

People in other countries were also horrified by the injustice of the ongoing chemical pollution story. A leading American photojournalist, W. Eugene Smith, lived in Minamata in the early 1970s and took heart-breaking photos of people crippled by mercury poisoning. Smith’s photos were first published in June 1972, just as two Minamata patients stood on the stage and explained mercury poisoning, in halting and unsteady words, at the United Nations conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm (Yorifuji, Tsuda, & Harada, 2013).

In the end, newspapers in Japan and the rest of the world were slow in recognizing the novelty and severity of the problem. Alternative media – magazine photography and documentary filmmaking – were the most effective in explaining the long struggle for victims’ rights in Japan.

The controversy persists many decades later. While several thousand victims did reach a settlement with the government and Chisso, other cases and other aspects of the controversy are ongoing. Some historians maintain that the Minamata episode aided in the democratization of Japan and the emergence of environmental journalism on a global scale (George, 2001).

Brazil 1960s-1980s

Randau Marques never imagined that anyone would object to an article he wrote in 1966 about lead poisoning among the cobblers of his small city of Franca, located halfway between Sao Paulo and Brazilia. They had been holding lead-alloy shoe nails between their lips as they worked, and the lead was causing neurological symptoms, Marques reported. But the 17-year-old quickly found himself before a military tribunal. He was imprisoned, labeled as a Communist, and tortured with electric shocks.

After a relatively short but painful jail term, Marques decided he would not back down. He began working in environmental journalism for the newspapers Jornal da Tarde and later for O Estado do Sao Paulo. He also founded the nonprofit Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science (SBPC). It was one way to keep the military from throwing him in jail again, he said.

“The [Brazilian] military regime, I discovered, saw in the scientist a kind of shaman who could provide gifts like the atomic bomb,” Marques said in a 2005 interview. “The SBPC was launched to bring together the entire resistance movement against dictatorship and the defense of citizenship – Or at least, against the torture and the rampant idiocy that still plagues us today.”

“I always worked with this concern not to stop the struggle, that is, to continue, to make journalism a [way] to end the whole picture of torture, violence, invasion, rape, that marked my life and the life of my generation. And that’s what I tried to do,” he explained to an interviewer in 2005.

One of Marques’ major exposés of the 1970s involved the “valley of death,” the Cubatão foundry and refinery center, where birth defects and cancers stalked the population. He also worked on some of the first stories about deforestation in the Amazon, about the genocide of the Yanomami Indians. “It was not environmental journalism, it was science journalism,” Marques said. “Our strategy [was] to hide in good science so that we would not have to answer to the censors, in my case, or to the courts of inquisition still assembled at that time.”

Marques’ experience was not surprising given Brazil’s antipathy to environmental protection in the 1960s and 1970s. The military government refused the basic premise of the 1972 Stockholm conference declaration, claiming that they had a right to unlimited industrial development (Barros, 2017). This was, in effect, an invitation to companies that would be attracted by Brazil’s cheap labor, artificial social stability, controls over workers and unions, and exemptions from expensive anti-pollution technology. Yet the pro-development rhetoric was often based on national pride and a profusion of natural resources and beauty that was part of Brazil’s identity.

The Cold War and environmental journalism 1970s-1980s

As wire services and broadcast unions brought the world together in the 1950s and 1960s, the superpowers – the US and the USSR – saw environmental issues as part of the Cold War competition.

Unlike the Brazilian dictatorship, which could thumb its nose at world opinion in 1972, both the US and the USSR, and their allies, “were aware of the importance of the mass media in the East-West ideological competition.” Environmental discussion “had to transcend Cold War propaganda and . . . demonstrate its responsible stance in international relations before a global public.” (McNeill & Unger, 2010).

With two systems in competition, and the global public as a witness, environmental issues took on a protected mantle, and activists felt they had room to maneuver.

In South Africa, still under apartheid rule, the Johannesburg Star launched the Cleaner Air, Rivers and Environment (CARE) campaign on March 10, 1971. CARE exposed pollution, soil erosion, diminishing wildlife, population explosion, and the overexploitation of natural resources (Steyn, 1998).

In India in the mid-1970s, a chemical plant caused fish kills in the southeastern state of Goa, which led to protests and some of the first experiences with environmental journalism, according to Frederick Noronha, writing in the 2008 book, Green Pen, Environmental Journalism in India and South Asia. “We were shocked by what we saw,” Noronha wrote of beaches filled with thousands of dead fish. “As we saw it then and continue to do so now, this was a battle against human greed, especially in those crucial years of the 1980s and 1990s” (Noronha, F., 2010, p 80).

In Thailand, mass demonstrations protesting the Nam Choan dam in Kanchanaburi from 1982 to 1984 represented the first time that activists could express themselves after the 1976 coup, and news coverage was permitted alongside the demonstrations (Quigley, 1995).

India, Bhopal, and the green revolution

One of the biggest environmental stories of the late 20th century in the developing world was the partial success of the Green Revolution and the associated disasters of Bhopal and general pesticide poisoning. While the strategy of highly mechanized and artificially fertilized farming led to a great deal more food production, it also eliminated traditional farming methods and contributed to groundwater contamination. By the 21st century, there were also concerns about premature deaths from pesticides.

Perhaps the biggest environmental news coming out of India in the 20th century was the Dec. 2, 1984 chemical disaster at Bhopal, a city of about two million people in central India. At least 10,000 people died and half a million were seriously injured when 40 tons of methyl iso-cyanate leaked from a tank and spread out over the city without any alarm or warning from the plant. Media coverage focused on the unprecedented scale of the disaster and various relief activities but communication of both engineering and medical information was severely constrained by public relations and legal liability concerns (Fortun, 2004).

While international news coverage waned, Indian media continued to focus on mass protests on behalf of victims and efforts to investigate and punish Union Carbide, the company responsible for the disaster. Ever sensitive to issues with its image, the Indian government was able to control television coverage through state-owned media but was not able to control independent newspaper coverage. However, Indian media lacked expertise to understand the legal, scientific, and technical aspects of the disaster, which was seen as turning into “a bonanza for fly-by-night operators, doctors, lawyers, self-led social workers, and everyone other than the victims of the tragedy.” Coverage peaked in 1989 when an Indian court-led settlement was announced and survivors reacted with anger (Sharma, 2014, p. 151).

With new communications technologies and the liberalization of some policies in the 1990s, the Indian media landscape became more open. Yet official sources and routine anniversary stories became the norm outside the city of Bhopal, while inside the city of Bhopal, the vast scope of suffering required the establishment of an information bureaucracy that attempted to help people cope with the variety of legal, medical, and relief efforts.

“The media’s lack of preparedness for disaster journalism matched the government’s own approach to disaster management,” Sharma (2014) said. Controversy would occasionally rise up when chemical companies would engage in high-profile activities, such as sponsorship of the Olympics in 2012, but otherwise, the controversy has been forgotten and lessons that might have applied to “other slow and silent Bhopals” have been lost.

The most significant “slow and silent Bhopal” involves the impact of pesticides (such as those being produced at Bhopal) on public health, especially through groundwater contamination, as well as the impact on traditional agriculture and India’s agricultural infrastructure. Lyla Bavadam, writing the 2010 book Green Pen, noted that environmental journalists should have been more aware of how the Green Revolution pushed out small farmers: “The introduction of something as seemingly simple and helpful as high yield rice resulted in social, health and environmental imbalances.” What this meant is that environmental journalists realized they needed a deeper approach to an enormous story. “While there is a serious need to use science in environmental journalism, there is as strong a need to question science” (Bavadam, 2010, p8).

Amrita Chaundhry, agricultural correspondent for the Indian Express, told the BBC in 2007: “The balance sheet of the Green Revolution is that, yes, we are feeding the mouths. India no longer has to ask for food aid from other nations. But the fact is that we are paying a very heavy price for agriculture at this present moment” (Doyle, 2007). Aside from the Bhopal disaster, everyday exposure to pesticides is now a leading cause of mortality in Bangladesh, in India, and in many developing countries that welcomed the Green Revolution (IRIN, 2010).

Environmental journalism in China

China’s experience with the Green Revolution, and with environmental journalism as a whole, was entirely different from India and most of the developing world.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the “problem” associated with pesticides in China was often described as a lack of supply. However, in places where insecticides were available, people quickly began observing the downside to their overuse. Chinese insect scientists had deep connections to international science and were alert to the problems of pest resistance and chemical toxicity. They also had more respect for rural people and their traditions, and thus, the net effect was to broaden China’s approach to agriculture in general (Schmalzer, 2016).

The Chinese media system has been entirely under the control of the Communist party. During the first decades after the revolution of 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was established, no information that was remotely critical was ever allowed to escape its orbit. For example, it took decades for the world to learn about the catastrophic collapse of 62 separate hydroelectric dams, including the Banqiao dam, during a typhoon that hit China on August 7, 1975. The death toll was estimated between 85,600 and 230,000 people.

The disaster was a state secret for years, and even after China Environment News was launched in Beijing in 1984, highly critical incidents such as the Banqiao disaster were not mentioned.

Dai Qing, who was a reporter and columnist for the Guangming Daily (Enlightenment Daily) in the 1980s, was concerned about the dams. She considered herself a patriot and, at one point, said she would be glad to die for Mao Zedong. She was trusted and was often the first Chinese journalist to discuss dissidents such as astrophysicist Fang Lizhi. But the trust eroded after she openly questioned hydroelectric dam construction programs.

Dai Qing found that many of the dams had been badly built during the high tide of socialism in the 1950s, and she noted that one of China’s top scientists warned that the dams “would produce a disaster of gigantic proportions beyond imagination” (Topping, 2015, p. xv).

But as she began to interview scientists and engineers for stories about the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River in the 1980s, she began to think of it as “the most environmentally and socially destructive project in the world.” Her book Yangtze! Yangtze! was published in February 1989, and at the time was taken to be a sign that China’s government was liberalizing discussion of politics, especially around environmental issues. This same liberalization around environmental issues was taking place in other areas of the world, especially the USSR.

However, Chinese authorities decided the country was not ready for liberalization and crushed the fledgling democracy movement in the Tiananmen Square massacre of June 1989. Dai Qing’s book was banned at the same time. It was published in the United Kingdom five years later. (Qing, 1994).

Not all environmental topics were banned in China. In 1993, an environmental news campaign “Across China Environmental Protection Centenary Action” involved more than 6,000 reporters from local to national news organizations. Stories included resisting garbage from abroad, cleanup activities along the Huaihe River and Lake Taihu, and enforcement of environmental laws. China Central Television also had “Earth Story” broadcast every night. The Three Gorges Dam was not covered, and yet in 2003, plans to create a new hydroelectric system on the Nujiang River in southwestern China were tabled due to public relations campaigns by Chinese non-governmental organizations whose perspectives were reported in the media and shared through social media campaigns (Liu, 2011).

Open controversies about chemical pollution in Xiamen in 2007, along with the Chinese government’s Environmental Information Disclosure Decree of 2008, led many scholars to anticipate an expansion of a “green public sphere” (Keeley & Yisheng, 2012). “I heard messages of progress and hope,” said Khanh Tran-Thanh, who reported on a panel of experts discussing the 2012 book Green China.

Chinese journalists have been aware of a need to enlarge the focus on the environment to include the human and economic impacts of environmental regulations – to cover the “larger environment” (Yu, 2002). Interviews with 42 environmental journalists between 2011 and 2013 showed that they believe in their work. They often assume advocacy roles and use angles that depart from the official state lines. They experience only a few reporting restrictions, they say, but they still have to deal with censorship (Tong, 2015).

In 2015, a two-hour documentary by former state television journalist Chai Jing called “Under the Dome” sharply questioned the corruption underlying air pollution in China. The documentary was made available through YouTube and posted on the People’s Daily website for a week but then banned by the Communist party (Mufson, 2015). China’s environmental protection minister said the documentary was comparable to Rachel Carson’s influential book Silent Spring (Wildau, 2015).

Chinese media are complex. Government control remained strong in the 2008–2013 timeframe. Some good was seen in the media’s potential for airing problems and easing social tensions, according to China’s Environment and China’s Environmental Journalists (De Burgh & Rong, 2013).

And yet, with crackdowns on dissent and independent journalism around 2016, many young reporters are discouraged and getting out of the business, according to a Guardian newspaper correspondent (Phillips, 2016).

The 1992 Rio Earth summit and beyond

International concern about development in the Amazon grew in the 1980s and was especially fueled by reports of hundreds of murders of native people, environmentalists, and human rights advocates, including the 1988 murder of rubber tapper leader Chico Mendes. In 1989, a newly elected Brazilian president, Jose Sarney, responded with more environmentally friendly rhetoric and promises to investigate the murders (De Barros, 2017). Also that year, Brazil agreed to host the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development, called the “Earth Summit,” in Rio de Janeiro. And Brazil created a 9.4-million-hectare reserve for the Yanomami natives in 1991, which, along with other environmental initiatives, won promises of more than a billion dollars in loans and other international initiatives (Rabben, 2004).

The Rio Earth Summit involved more than 100 national leaders and about 10,000 journalists from around the world. It produced a forward-looking treaty pledging nations to environmental protection in biodiversity, forestry, and countering climate change. Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development “seeks to ensure that every person has access to information, can participate in the decision-making process and has access to justice in environmental matters with the aim of safeguarding the right to a healthy and sustainable environment for present and future generations” (United Nations, 1992). Many journalists felt that it was a turning point, a rare moment of appreciation for environmental journalists around the world, who had been struggling for legitimacy and recognition within their own profession and in dealing with government organizations.

Mexico Guadalajara gas explosion 1992

Newspaper reporter Alejandra Xanic did not believe the assertion from officials in Guadalajara that fumes from a major natural gas leak had been dispersed. The reporter stayed on site, interviewing workers and trying to piece a story together. The next day, April 22, 1992, a blast ripped through 26 blocks of the city and killed more than 200 people. The blast followed the same path that had been predicted in Xanic’s newspaper Siglo 21 that morning. The government’s failure to respond to the emergency, to warn people to evacuate, and to deal honestly with the media, became an election issue in subsequent years. For the first time, the dominant PRI party lost city and state elections, along with an enormous amount of national credibility.

For Mexican journalists, embattled by government and drug lords, attempting to escape a history of corrupt and cozy relations with the government, here was proof that a public service mission of environmental journalism could make a difference (Hughes, 2003). And yet, unless there is a crisis, environmental reporting in Mexico is virtually dormant, according to a 2016 study by Manuel Chavez and others (Chavez, Marquez, Flores, & Guerrero, 2018).

Nigeria – Ken Saro-Wiwa 1995

One of the most dispiriting moments in the history of African environmental journalism was the execution of journalist and playwright Ken Saro-Wiwa on November 10, 1995. In addition to writing about Nigeria’s environment, Saro-Wiwa had been an organizer and president of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People, a minority group living in the Niger Delta, where the impacts of oil pollution are so severe that farming and fishing are virtually impossible.

Saro-Wiwa helped escalate protests against the oil industry and the Nigerian government. An editorial in the Sunday Times of Lagos said that while history is on the side of the protesters, “they are faced by a company – Shell – whose management policies are racist and cruelly stupid, and which is out to exploit and encourage Nigerian ethnocentrism” (Saro-Wiwa, 1991).

Because of his advocacy, he was awarded the Right Livelihood Award and the Goldman Environmental Prize. But the response from the Nigerian government was repression, with random killings, the destruction of villages, and arrests of activists on trumped-up charges. Saro-Wiwa was also arrested and charged with a murder that took place on a day that he was actually in military custody. He was convicted by a military court and sentenced to death by hanging. Despite pleas for clemency from world leaders – including UN Secretary General Boutros-Boutros Ghali, President Bill Clinton, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, South African President Nelson Mandela, and many others – Saro-Wiwa was executed, sending shock waves through the press and the environmental movement.

Before he was executed, Saro-Wiwa said: “I’ve used my talents as a writer to enable the Ogoni People to confront their tormentors. I was not able to do it as a politician or a businessman. My writing did it . . .” (Agbo, 2018).

Environmental journalism continues in Nigeria and the rest of Africa, but is often seen as a low prestige reporting beat (Uzochukwu, Ekwugha, & Marion, 2014). It is often dominated by international climate change reporting to the exclusion of other topics closer to home (Emenyeonu & Mohamad, 2017).

Occasional bright spots often come from non-traditional media, such as “Africa Uncensored” distributed through YouTube. While a series on lead poisoning in the Owino Uhuru settlement of Mombasa, Kenya, had problems reporting medical standards, a true concern for people exposed to lead from battery recycling is evident. The lead poisoning story is the single environmental story in a 2016 list of 100 pieces of Kenyan journalism published in Owaahh online magazine.

Fukushima and the Japanese media 2011

When four nuclear reactors exploded at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan on March 11, 2011, Japanese newspapers and television dutifully repeated the official government line that there was no problem. Today, the media’s acceptance of the cover-up is widely criticized.

Japanese people and media felt victimized by the Japanese government policy of blocking access to the news of the accident. To find out what really happened, they sought foreign media sources such as the BBC (Imtihania & Marikoa, 2013).

While Japan’s media are nominally free, relations between mainstream media and the government are often considered too close. According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), journalists in Japan can’t fulfill their watchdog role because of the influence of tradition and business interests. A climate of mistrust toward the press has been heightened since Shinzo Abe became prime minister in 2012. Journalists who are critical of the government or cover “antipatriotic” subjects, such as the Fukushima Daiichi disaster, are harassed and may be imprisoned under a “Specially Designated Secrets” law (Reporters Without Borders, 2018a).

Even Tokyo’s Asahi Shimbun, the world’s second-largest newspaper with a daily circulation of 6.8 million, considered the intellectual flagship of Japan’s political left, has pulled back from its investigations into Fukushima following harsh right-wing attacks led by Abe (Fackler, 2016).

Deteriorating international conditions

When two reporters for The Cambodia Daily followed environmental activist Chut Wutty into the Cardamom Mountains on April 26, 2012, they expected to investigate an illegal logging operation. Instead, they returned to the newsroom, deeply shaken, to report that Wutty had been killed by police who were guarding the operation (Beller, 2017). World opinion was outraged, but there were no arrests (Cohen, 2017).

Five years later, in September 2017, the Cambodian government closed down The Daily and censored all remaining news operations. Today in Cambodia, there is no one to take Chut Wutty’s place. No one living in Cambodia speaks up against illegal logging. Even if they did, no newspaper could report it, much less describe the assassination of an environmental activist.

Cambodia’s problem is an example of a deterioration in conditions as environmental journalists are increasingly imprisoned, assaulted, and murdered by state and private interests for exposing problems with mining, forestry, and endangered species.

The problem was recognized in 2009 at the Copenhagen Climate Summit, when 14 international, regional, and national press freedom organizations called for world leaders to reaffirm their pledge to Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration and Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. “We urge all governments to practice transparency in access to information and to protect journalists reporting on environmental issues and climate change . . .” the declaration said (Reporters Without Borders, 2009).

In many countries the situation has utterly deteriorated. In Mexico, for example, between 2000 and 2019 over 130 journalists were killed (Avila, 2019; Seelke, 2018). Protesting the murders with impunity, the Mexican Environmental Journalists Network said: “We demand justice. . . . Journalism’s social role in building democracy and in aiding the development of peoples and nations is recognized worldwide. Violence against professional journalists in Mexico cannot continue to go unpunished and society cannot remain silent” (REMPA, 2012). While a Special Prosecutor for Attention for Crimes Against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE) was appointed in 2017, two years into its investigations, very little has been accomplished and the rate of violence had not slowed.

In recent years, environmental beats have turned out to be among the most dangerous in journalism, especially in the global South where the news media of most countries is either partly free or not free (Freedman, 2018). Forty journalists were killed reporting environmental news between 2005 and 2016 according to a Poynter Institute Study (Warren, 2016). Journalists covering environmental protests are routinely attacked by soldiers and police (Reporters Without Borders, 2018b).

Some victories are worth noting, for example, “Under the Dome” in China and non-mainstream media efforts in Africa and Latin America. But the continuing assault on journalists, despite protests and special prosecutors and widespread human rights concerns, is leading to a crisis situation. Overall, 1,300 journalists have been killed for their work worldwide between 1992 and 2019. “Although their voices have been silenced, we are speaking up,” said the Committee to Protect Journalists in a 2019 report.

“The space for environmental journalism is shrinking,” said Keya Acharya and Frederick Noronha in Green Pen, a 2010 book about environmental journalism in India. If we hope that the next generation of journalists will cover the environment, then “the least we could do is not forget our history” (Acharya & Noronha, 2010).

References

Acharya, K., & Noronha, F. (Eds.). (2010). The green pen: Environmental journalism in India and South Asia. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Africa Uncensored. (2016). Lead poisoning in Owino Uhuru, Mombasa [Video]. Retrieved from www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWU6AsfhYs0&spfreload=10

Aronczyk, M. (2018). Environment 1.0: Infoterra and the making of environmental information. New Media & Society, 20(5), 1832–1849.

Asahi Shimbun. (1957). Mysterious illness in Kumamoto, patients are unwell even after medical treatment, study by the Health and Welfare Minister. Retrieved March 15, 2018, from www.asahi.com/special/kotoba/archive2015/mukashino/2014021800002.html

Avila, I., & Arceo, R. (Eds.). (2019). Protocolo de la Impunidad en Delitos Contra Periodistas. Mexico City, MX: Article Nineteen.

Barros, A. T. (2017). Brazil’s discourse on the environment in the international arena, 1972–1992. Contexto Internacional, 29(2), 421–442. Retrieved from https://articulo19.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/A19-2019-InformeImpunidad_final_v3.pdf

Barton, F. (1979). The press of Africa: Persecution and perseverance. London, UK: Macmillan.

Bavadam, L., (2010), “Environmental stories, among the most challenging,” in Acharya, K., & Noronha, F. (Eds.). (2010). The green pen: Environmental journalism in India and South Asia. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Beller, T. (2017, September 12). The devastating shutdown of the Cambodia Daily. The New Yorker. Retrieved from www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-devastating-shutdown-of-the-cambodia-daily

Brendebach, J., Herzer, M., & Tworek, H. (Eds.). (2018). International organizations and the media in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, exorbitant expectations. New York, NY: Routledge.

Celarent, B. (2012). Rebellion in the Backlands by Euclides da Cunha [Book review]. American Journal of Sociology, 118(2), 536–542.

Chai Jing. (2015). Under the dome [Investigative video report]. Retrieved from www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5bHb3ljjbc

Chavez, M., Marquez, M., Flores, D. J., & Guerrero, M. A. (2018). The news media and environmental challenges in Mexico: The structural deficits in the coverage and reporting by the press. In B. Takahashi, J. Pinto, M. Chavez, & M. Vigón (Eds.), News media coverage of environmental challenges in Latin America and the Caribbean (pp. 19–46). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cohen, J. (2017, April 26). Five years since the murder of our friend Chut Wutty [Blog]. Global Witness. Retrieved from www.globalwitness.org/en/blog/five-years-murder-our-friend-chut-wutty/

Committee to Protect Journalists. (2019). Global campaign against impunity. Retrieved from https://cpj.org/campaigns/impunity/

Corrêa, M. S. (2010, August 15). Environmental journalism in Brazil’s elusive hotspots: The legacy of Euclydes Da Cunha. Journal of Environment and Development, 19(3), 318–334.

De Barros, A. T. (2017). Brazil’s discourse on the environment in the international arena, 1972–1992. Contexto Internacional, 39(2), 421–442. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2017390200011

De Burgh, H., & Rong, Z. (2013). China’s environment and China’s environmental journalists. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Doyle, M. (2007, March 29). The limits of a green revolution? BBC World Service. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/in_depth/6496585.stm

Emenyeonu, O. C., & Mohamad, B. B. (2017). Covering environmental issues beyond climate change in Nigerian Press: A content analysis approach. Jurnal Liski, 3(1), 1–23. Retrieved from www.researchgate.net/publication/318560653_Covering_Environmental_Issues_beyond_Climate_Change_in_Nigerian_Press_A_Content_Analysis_Approach

Fackler, M. (2016, May 27). The silencing of Japan’s Free Press. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/27/the-silencing-of-japans-free-press-shinzo-abe-media/

Facts on File. (1973, March). Environment: 80 countries in wildlife pact. Facts on File World News Digest.

Fortun, K. (2004). From Bhopal to the informating of environmentalism: Risk communication in historical perspective. Osiris, 19, 283–296.

Freedman, E. (2018). In the crosshairs: The perils of environmental journalism. Conference Paper, Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication.

Gandhi, M. K. (1909). Hind Swaraj [Home rule]. Natal, IN: The International Printing Press.

George, T. S. (2001). Minamata: Pollution and the struggle for democracy in postwar Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center.

Guha, R., & Martínez-Alier, J. (1997). Varieties of environmentalism: Essays North and South. London, UK: Routledge.

Hochschild, A. (1998). King Leopold’s ghost: A story of greed, terror, and heroism in colonial Africa. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Hughes, S. (2003). From the inside out: How institutional entrepreneurs transformed Mexican journalism. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 8(3), 87–117.

Imtihani, N., & Marikoa, Y. (2013). Media coverage of Fukushima nuclear power station accident (a case study of NHK and BBC World TV stations). The 3rd International Conference on Sustainable Future for Human Security, SUSTAIN 2012. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 17, 938–946.

IRIN. (2010, January). Pesticide poisoning takes its toll. IRIN. Retrieved from www.irinnews.org/report/87773/bangladesh-pesticide-poisoning-takes-its-toll

IRIN. (2019). About us. IRIN. Retrieved from www.irinnews.org/content/about-us

Japan Ministry of the Environment. (2013). Lessons from Minamata disease and mercury management in Japan. Retrieved from www.env.go.jp/chemi/tmms/pr-m/mat01/en_full.pdf

Kamau, J. (2009, November 9–13). Seeds of discord: The Kenyatta family records. Daily Nation, Nairobi, Kenya.

Kapchanga, M. (2016, February 2). Kenya’s under fire journalists refuse to be cowed. African Arguments. Retrieved from https://africanarguments.org/2016/02/02/kenyas-under-fire-journalists-refuse-to-be-cowed/

Kaushik, A. (2018). Mahatma Gandhi and environmental protection. Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal and Gandhi Research Foundation, Jalgaon. Retrieved from www.mkgandhi.org/articles/environment1.htm

Keeley, J., & Yisheng, Z. (Eds.). (2012). Green China: Chinese insights on environment and development. London, UK: International Institute for Environment and Development. Retrieved from http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17509IIED.pdf

Liu, J. (2011). Picturing a green virtual public space for social change. Chinese Journal of Communication, 4(2), 137–166.

Maloba, W. O. (2018). Kenyatta and Britain: An account of political transformation, 1929–1963. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

McNeill, J. R., & Unger, C. R. (2010). Environmental histories of the cold war. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Morel, E. D. (1904). King Leopold’s rule in Africa. London, UK: William Heinemann.

Mufson, S. (2015, March 16). This documentary went viral in China. Then it was censored. It won’t be forgotten. Washington Post. Retrieved from www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2015/03/16/this-documentary-went-viral-in-china-then-it-was-censored-it-wont-be-forgotten/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.8dd02fcc641e

Munshi, K. M. (1952, October 23). Inaugural address: The production and use of power alcohol in Asia and the Far East. Report of a Seminar Held at Lucknow, India. Organized by the Technical Assistance Administration and the Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, United Nations, New York, NY.

Noronha, F., “Tourism and beyond: Does environmental journalism matter?” in Acharya, K., & Noronha, F. (Eds.). (2010). The green pen: Environmental journalism in India and South Asia. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ogan, C. L. (1980). Development journalism and communication: The status of the concept. Conference Paper, Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED194898.pdf

Pearce, F. (2010, January 19). Why Africa’s national parks are failing to save wildlife. Yale Environment 360. Retrieved from https://e360.yale.edu/features/why_africas_national_parks_are_failing_to_save_wildlife

Phillips, T. (2016, February 11). China’s young reporters give up on journalism: “You can’t write what you want.” The Guardian. Retrieved from www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/12/china-journalism-reporters-freedom-of-speech

Quigley, K. F. F. (1995). Environmental organizations and democratic consolidation in Thailand. Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 9(2), 1–29.

Rabben, L. (2004). Brazil’s Indians and the onslaught of civilization: The Yanomami and the Kayapo. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

REMPA. (2012, May 24). Red Mexicana de Periodistas Ambientales: Statement on killings of Mexican journalists. Society of Environmental Journalists. Retrieved from www.sej.org/library/rempa-statement-killings-mexican-journalists

Reporters Without Borders. (2009, December 11). Call to action to protect environmental journalists. Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved from https://rsf.org/en/news/call-action-protect-environmental-journalists

Reporters Without

Reporters Without Borders. (2018a). Japan. Retrieved from https://rsf.org/en/japan

Reporters Without Borders. (2018b). Violence against reporters covering mine protest in Northern Honduras. Retrieved from https://rsf.org/en/news/violence-against-reporters-covering-mine-protest-northern-honduras

Reyes, F. A. (1908, October 30). Aves de Rapiña [Birds of prey]. El Renacimiento.

Saro-Wiwa, K. “The coming war in the delta,” Nov. 25, 1990 column in The Sunday Times, Lagos, Nigeria. Reprinted in Similia: Essays on anomic Nigeria, (1991). Saros Internartional Publishers.

Savio, R. (2014, August 22). International relations, the U.N. and Inter Press Service [Opinion]. Inter Press Service News Agency. Retrieved from www.ipsnews.net/2014/08/opinion-international-relations-the-u-n-and-inter-press-service/

Schmalzer, S. (2016). Red revolution, green revolution: Scientific farming in socialist China. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Schmidt, J. J. (2019). Water: Abundance, scarcity, and security in the age of humanity. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Seelke, C. R. (2018, May 17). Violence against journalists in Mexico: In brief. Congressional Research Service, Washington, DC.

Sharma, S. (2014). Indian media and the struggle for justice in Bhopal. Social Justice, 41(12), 146–168.

Steyn, M. S. (1998). Environmentalism in South Africa, 1972–1992: An historical perspective (Master’s dissertation). University of the Free State. Retrieved from http://scholar.ufs.ac.za:8080/xmlui/handle/11660/6267

Togashi, S. (1999, June 3). The relationship between inquiry into the cause of Minamata disease and social action preventing the epidemic [Abstract]. Kumamoto University. Retrieved from www.hf.rim.or.jp/~dai-h/minamata/MINABG1.html

Tong, J. (2015). Investigative journalism, environmental problems and modernization in China. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Topping, A. R. (2015). Foreword: The river dragon has come! In Dai Qing (Au.), The river dragon has come! The three gorges dam and the fate of China’s Yangtze River and its people (p. XV). New York, NY: Routledge.

UNEP United Nations. (2006). Environmental reporting for African journalists: A handbook of key environmental issues and concepts. Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP.

United Nations. (1949, August 17–September 6). Proceedings of the United Nations scientific conference on the conservation and utilization of resources, Lake Success, NY. Retrieved from https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015027769119;view=1up;seq=50

United Nations. (1972, June 16). Declaration of the United Nations conference on the human environment, Stockholm. Retrieved from http://legal.un.org/avl/ha/dunche/dunche.html

United Nations. (1992). Report of the UN conference on environment and development. Retrieved from www.un.org/documents/ga/conf151/aconf15126-1annex1.htm

Uzochukwu, C. E., Ekwugha, U. P., & Marion, N. E. (2014). Media coverage of the environment in Nigeria: Issues and prospects. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Reviews, 4(4), 22–30.

Villon, A. F. (1980). INFORTERRA: A global network for environmental information. Environment International, 4(1), 63–68. Retrieved from www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0160412080900951

Warren, J. (2016). One of the most dangerous beats in journalism, revealed. Vanity Fair. Retrieved from www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/09/one-of-themostdangerous-beats-in-journalism-revealed

Washington Post. (1900, December 11). Succor for mammals: Africa converted into a vast game preserve [Editorial]. Washington Post, p. 27.

Wildau, G. (2015, March 3). Smog film captivates Chinese internet. Financial Times. Retrieved from www.ft.com/content/de190a92-c0b0-11e4-876d-00144feab7de

Yasui, Y., & Gerow, A. (1995, October 3). Documentarists of Japan, No. 7: Tsuchimoto Noriaki [Interview]. Documentary Box #8, Tokyo, Japan. Retrieved from www.yidff.jp/docbox/8/box8-2-e.html

Yorifuji, T., Tsuda, T., & Harada, M. (2013). Minamata disease: A challenge for democracy and justice. In European Environment Agency. (Ed.), Late lessons from early warnings: Science, precaution, innovation (pp. 92–120). Copenhagen, DK: European Environment Agency.

Yu, S. (2002). Environmental reporting in China. Nieman Reports. Retrieved from https://niemanreports.org/articles/environment-reporting-in-china/